LINDA LIM

Linda Lim reflects on decades of living abroad while pursuing an intellectual passion for — and personal commitment to — the development and well-being of Singapore.

Singapore academics often ask me: Why did you work overseas, and how did you manage to study Singapore from there? How did you survive as a critic of the government? Why have you remained a Singaporean after spending most of your life abroad?

The answers to all these questions intersect. I’m a fourth-generation Singaporean, I care about my country, and I would not have made my career abroad if it had been possible to contribute by staying home. Becoming an expatriate — not an émigré — was not something I planned. It happened because of developments in Singapore itself.

My expatriate journey started unexpectedly. The mass political detentions of 1977 ensnared several of my friends — journalist Ho Kwon Ping, orthopedic surgeon Dr. Ang Swee Chai and others — who were detained without trial and never charged with any offence, because they had committed none. I had joined the informal social group of young professionals (including a lawyer, an architect, civil service engineers and economists) while doing field research for my economics PhD dissertation on the export-oriented multinational electronics industry in Singapore and Malaysia. We shared a common interest in our countries’ development, so got together to read articles, discuss current events, play music, enjoy beach excursions and other outings. What we did not do was plot to overthrow the government by violent means, as Kwon Ping was coerced into confessing on TV before he was released.

The arrests of Lim’s friends in Singapore under the Internal Security Act in 1977, which made it to the front page of the New York Times (right), was a turning point in her life.

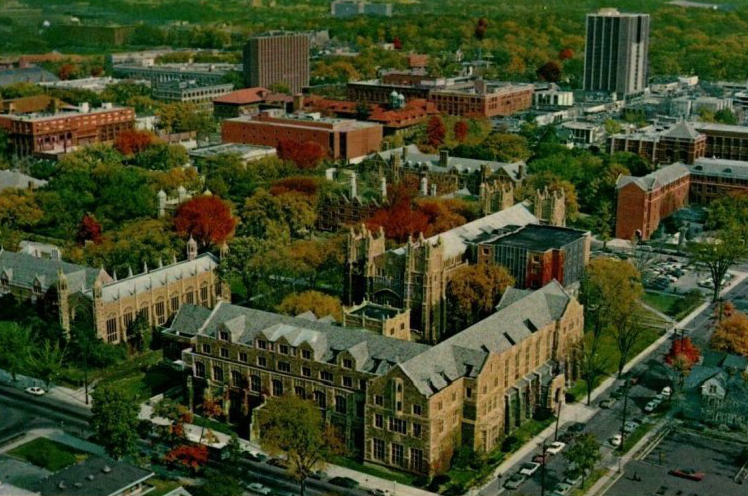

The arrests took place after I had returned to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor to write up my research. I had chosen this University because it had a rare and leading Center for Southeast Asian Studies, and “the only tenured radical professor in a top ten economics department”, Thomas Weisskopf. I learned this while doing my Masters at Yale, where I had joined the Union for Radical Political Economics (URPE). My interest in “non-mainstream” economics had been whetted by my heterodox undergraduate education at the University of Cambridge.[1]

Following the arrests, my family and friends in Singapore urged me not to return to the academic job I had been offered at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. My Michigan professors helped me secure an interview at Swarthmore, a top liberal arts college. Since the arrests in Singapore had made it to the front page of The New York Times, I was asked, “Why are you on the job market at such an unusual time? Is it because of recent political developments in Singapore?” I accepted the tenure-track job of assistant professor of economics, not knowing that Swarthmore students had been agitating for the hire of a radical economist and some considered me “not radical enough”. There I taught courses in introductory economics, development economics, political economy and the history of economic thought.

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, pictured on a 1970s postcard. Linda Lim completed her PhD there in 1978 and returned to a faculty position in its business school.

In 1980-81, I was informed that it was safe to return to Singapore. I joined as a research fellow at the then University of Singapore’s Economic Research Centre (ERC), which carried out research for government and international agencies. I quit my job at Swarthmore. My American husband, an academic specialist on Southeast Asia, was happy for us to live in Singapore, and our daughter, newly born there, was a citizen herself.

Alas, gender discrimination made this impossible—the same discrimination which would have denied my daughter citizenship if she had been born abroad to a female citizen (but not to a male). At the time, female civil servants (including academics) were denied healthcare benefits for our spouses and children, and my husband could not get permanent residence based on our marriage, unlike the foreign wives of Singaporean male colleagues. Nor could I apply for a HUDC flat with a foreign husband.

So, faced with being without a home, family health insurance and a secure visa status for my husband, we returned to his tenured position at the University of Michigan, and the house in Ann Arbor he had designed and built around a pond filled with water-lilies, koi and goldfish, on four acres of forest land. We had been willing to give this up to relocate to Singapore. As it turned out, the ERC was shut down shortly after I left, so that job would have evaporated anyway.

A few years later, I experienced another four years of self-exile, after I published a commentary overseas critical of the 1987 Operation Spectrum mass arrests.[2] This, I was told, made the authorities “very angry”. One detainee, Vincent Cheng, had been among a small group of pastors-in-training I had given political economy lessons to in 1976, but that did not enter into my economics-based analysis.

In 2004, a delegation of Singapore university leaders visited my University. One visitor said, “I wanted to invite you to come home [to a senior administrative faculty position], but once I saw your house, and your relationship with your [Singaporean] students, I knew it was hopeless.” It was April, and thousands of daffodils were abloom in our woods garden. Later still, the parent of a Singaporean student asked “how much” our property was worth. When we guessed maybe half a million U.S. dollars, she said “My place already two million.” Visiting students occasionally exclaimed, “In Orchard Road this [property] would be a billion dollars!”

At home in Ann Arbor with the then Minister for Education, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, whose delegation visited the University of Michigan in 2004.

But is it really the cheap land and housing, and the relaxed lifestyle, which have kept me in Ann Arbor for half a century now? And if so, why have I clung on to my Singapore citizenship?

Psychologists, most notably Erik Erikson, pinpoint the adolescent years as critical to “identity formation”. At that age I attended Methodist schools in Singapore (as had one set of my great-grandparents and both my grandmothers). Today I remain close with a group of a dozen classmates from those years, seven still living in Singapore, with the rest in the U.K., U.S. and Canada.

More significantly, 1962 to 1968 were also the years of Singapore’s transformation from a British colony to a constituent state of Malaysia and then to a reluctant sovereign nation. When we joined Malaysia in 1963, my Secondary One class put on a musical pageant of a “Malaysian market” to celebrate. In 1965, when we separated from Malaysia, I vividly remember Lee Kuan Yew saying in a speech, “Pray God my successor is an economist”–to ensure our survival, which was then in doubt.

School ties: This 1934 photo (top) of former students of Methodist Girls School includes Linda Lim’s grandmothers, third from the right in the front row and second from the right in the back row. The bottom left photo shows Linda (middle, with glasses) in a pageant celebrating Merger with Malaysia in 1963. The bottom right photo, from 1966, shows her (bespectacled) and her friends on the school magazine’s editorial committee.

Determined to do my part, and fortunately loving economics as a subject, I read economics as an undergraduate, despite having been rejected for an Overseas Merit Scholarship. I was told the reason for this rejection was that all the candidates in my cohort were “girls” and the PSC had experienced too many previous female recipients not returning home due to marriage abroad. This turned out to be a lucky break – I would not be contractually obliged to enter government service after my studies.

I chose Cambridge in part because it was the alma mater of Lee Kuan Yew and Mrs. Lee, an alumna of my school who had been the Guest of Honor handing me my School Certificate at graduation. In 1971 in Cambridge, I met the Great Man himself. When I said I was studying economics and Mr. Lee appeared puzzled, Mrs. Lee asked gently, “You want to work for the Economic Development Board?”

Singapore’s economic development has certainly been my obsession since my years of “identity formation”, a subject I have pursued from handwritten undergraduate essays to my doctoral dissertation and beyond. Economic development, international business, Southeast Asian and Asian economies generally became the “cover” or rationale for my continuing to work on Singapore, which then as now is never big, important or generalizable enough to constitute a teachable or tenurable field on its own. I spent many years as a lecturer on yearly contracts teaching “core” subjects in international economics and business management, so I could do research and consulting for the United Nations and other international development agencies on Asian development. These were always relevant to Singapore, whether it was foreign direct investment, industrialization, or women in the labor force.

Teaching in 1992.

During my career, I raised millions of dollars in grants or what is called “soft money” from the U.S. federal government and foundation sources to develop courses and a program on Southeast Asian business at my University. Later, I became the director of our Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Some of my Asia-trained American former students have worked stints in Singapore: one became a Singapore citizen and another is the current Chair of the American Chamber of Commerce in Singapore. I also became an independent director on the boards of two U.S. multinational electronics companies with operations in China and Singapore.

These activities kept me present and engaged in Singapore and our neighboring countries. I spent time several weeks if not months there each year. Additionally, my networks were greatly expanded through Singapore-based students and alumni of the University of Michigan. These now number about 1,400 (including DPM Lawrence Wong), and I produce a quarterly newsletter for them. The University’s alumni network, and my own scholarly linkages, also extend into neighboring countries of Southeast Asia, China and India, where my former students “in high places” or “close to the grassroots” are sources of useful connections and insider knowledge. For example, another former MBA student of mine heads the Singapore, Southeast Asia and South Asia operations of the Chinese investment bank CICC (China International Capital Corporation).

From top, left to right: Lim with alumni in Kuala Lumpur (2007), Singapore (2015), Singapore (2012) and Jakarta (2010), and with students in her Business in Asia class (2013).

So, I could pursue my Singapore passions from abroad, as an expatriate scholar-teacher and business practitioner. This of course owes much to globalization and technology. I also “spread the word” about Singapore far and wide through my professional activities and visibility, and created connections through my networks — for example, between leading Singapore civil servants and a top US economist in one case, and between MOE officials and top administrators at my University in another. I invited Singaporean Ambassadors Tommy Koh, Kishore Mahbubani, Chan Heng Chee, Ong Keng Yong and Ashok Mirpuri to speak at my University, as I did other ASEAN luminaries like Anwar Ibrahim (now Malaysia’s PM), the late Surin Pitsuwan (then ASEAN Secretary-General), and Airlangga Hartarto (now Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs).

I have served as a resource person to MOE’s Steering Committee on University Autonomy, Governance and Finance, and on the board of the NUS America Foundation for 15 years. Despite these services, when nominated in 2014 by the President of one of the local universities to be on their board of trustees, I was rejected by the powers-that-be. So much for “university autonomy”! Regardless, in 2017 I spent the last of my faculty research funds producing a lengthy memo on the challenges facing, and ways to promote more Singaporean faculty at our local universities, sharing it with MOE, and the leaders and trustees of local universities. Over the years, I have authored some 20 commentaries, in local (Straits Times, Channel News Asia) and international (Times Higher Education, South China Morning Post) media outlets on Singapore higher education, addressing the problems with rankings, the value of liberal arts education, threats to academic freedom, the need for more local Singaporean scholars and scholarship and more. I and Singaporean colleagues at the University of Michigan, Gunalan Nadarajan and Jessie Xi Yang, also shared our expertise on STEM vs humanities education in the Singapore media.

With husband L.A. Peter Gosling (1927–2023) in Burma (1982) and with friends Edilberto and Melinda de Jesus from the Philippines (2009). Gosling was a geography professor who conducted field research on rural development, water transportation and population resettlement in Southeast Asia, giving the couple another reason to stay connected with the region. In 2022, Pete and Linda established the Gosling-Lim Postdoctoral Fellowship in Southeast Asian Studies at the Association for Asian Studies.

When and why did I become tagged a “government critic”? I didn’t set out to be one. But I have always liked to think, and write, and argue. In 1976, I wrote several articles on the school system, with particular criticism of the practice of streaming.[3] With my friend Jacqueline Foo (later detained by the ISD but never charged), I also published a “counter review” in The New Nation attacking a sexist book review.[4] These articles sparked lively exchanges in the paper – Singapore news media was much freer then than it is now.[5]

Continuing in this vein, I contributed many articles to local and Asian regional business magazines, often with Pang Eng Fong, on economic topics.[6] These were usually offshoots of acadmic publications, including peer-reviewed journals and books, using standard disciplinary methodologies to analyze empirical data on Singapore gleaned from public sources and our own original research interviews. They were not particularly “radical”, though as is the norm for academics we enjoyed challenging conventional wisdoms. One of my most frequently cited papers is “Singapore’s Success: The Myth of the Free Market Economy” (Asian Survey, 1983), which merely described the strong role of the government in the economy, something with which no one in Singapore would disagree, but which often comes as a surprise to scholars and policymakers in the West.

It is not clear why and how I and others became labelled as “government critics”, when we are just doing our jobs as professionals, and “telling it like it is”, while focused on the long-term well-being of our country. In my case, perhaps it is because people, not least my own former students, are sometimes curious as to how a radical economist could end up as a business school academic and practitioner. But business is Capital with a capital C and, as an URPE colleague who became chief economist of a major Wall Street bank put it, “Only Marxists can truly understand Capital.” (He also said once, when we were discussing a Singapore government policy, “The Singapore government is one of my ten biggest clients worldwide. I am not going to tell them what they do not want to hear.”) Indeed, my training in Marxian economics proved useful much later when teaching state enterprise senior managers from China about capitalism (for “Made in China 2025”), just as my expertise on Southeast Asia was for teaching them about the region (for “Belt-and-Road Initiative”) — an opportunity that arose for me in Ann Arbor, not Singapore.

Today, scholarly analyses as well as policy-oriented discussions of capitalism as a “historical mode of production” embedded in political institutions (“power”) and social structures (“class”), and beset with contradictions (economic instability and inequality) — the nub of Marxist economic theory — have become central in mainstream public policy discourses. More generally, evaluating government policies to point out their flaws, risks, omissions, inadequacies, unexpected and unequal consequences is necessary if they are to be improved, and if progress is to be made beyond the status quo. This is just what academics, particularly applied economists and other social scientists, do. For a nationalist like myself, it is no less than an obligation.

Economist Pang Eng Fong (standing) collaborated with Lim on several publications. When Lim visited Singapore in 2018, Pang invited younger Singaporean academics to meet her at a gathering at his home. Lim co-founded AcademiaSG with three of them the following year.

Yet here is where being an expatriate has been critical to my own professional and political “survival”. Being in American academia affords me a precious privilege that colleagues in Singapore do not necessarily enjoy: freedom of expression. As a Singaporean economist said in 2008, “You are the only one whose income stream is not here — you must speak out.” My employment and income would not be in jeopardy if I criticized government policy—which was not thought to be the case for economists working in Singapore universities, government agencies, banks and corporations. He was referring to the massive surge in foreign labor imports, which local economists thought was economically, politically, socially and environmentally unsustainable (as Pang Eng Fong and I had suggested as far back as 1981). But that is far from the only issue on which my professional judgment has differed from “the official line” — a diversity of opinions which is the norm in advanced democracies, particularly in academia,[7] but often considered contentious in Singapore.

I believe my mildly dissident views are tolerated by the authorities because I live abroad. A permanent secretary once told me, “We like you because you understand us, but are not vested in the local system,” reflecting a regrettable mistrust of those who are. My published “contrarian” views may also serve as convenient evidence that free criticism is permitted. Research informants are sometimes more candid with me than they would be with a locally-based scholar, suspecting that the latter might have some unspecified agenda that might conflict with the informant’s, or the government’s, interest. And there is sometimes an unwarranted “halo effect” attached to Singaporeans considered to have “made it” abroad, especially in the hyper-competitive United States. I even once got to enjoy what has been dubbed the “ang moh treatment” which colleagues tell me is sometimes afforded visiting senior foreign scholars — car-and-driver, MFA staff escort, meetings with Ministers — and, perhaps more unusually, a lunch hosted by President Halimah Ya’acob at the Istana.

So why have I not given up my Singapore citizenship and become an American?

Obviously because my identity, formed in adolescence, has been progressively enhanced by my life, work and associations since then. After 55 years abroad, I still feel like a Singaporean, and retirement has afforded me even more time to obsess about my country and engage with compatriots, including on WhatsApp day and night. In 2019, I co-founded the academic collective AcademiaSG which promotes scholarship “of/for/by Singapore”, and champions academic freedom and civic engagement by academics. This happened in response to the passage of POFMA, when we marshalled a letter of concern to MOE signed by many international as well as local scholars knowledgeable about Singapore, including six past Presidents of the scholarly Association for Asian Studies, headquartered in Ann Arbor.

Lim co-founded Singaporeans-in-Michigan in 2019.

That same year, I co-founded the “Singaporeans-in-Michigan” group of overseas Singaporeans resident in the state of Michigan. These two groups embody and reflect different aspects of my Singaporean identity. AcademiaSG provides a platform for the airing of scholarly views that critically examine establishment orthodoxies, hopefully providing a counterpoint to official intolerance. “Singaporeans–in-Michigan” on the other hand, while not uncritical, celebrates our common identity with nostalgia and some of the romanticism that often colors expatriate communities’ views of their homeland.

Since then, I have penned or co-authored over 30 commentaries, covering a variety of Singapore-focused topics, including trade and exchange rate policies, the U.S. and China economies and international relations, higher education especially university rankings and academic freedom, foreign labor and wage policy, meritocracy, income inequality, race, fiscal policy, foreign reserves, and Singapore’s economic model. Though not a deep domain expert on all these subjects, I believe my generalist economics training can help elucidate them for the non-expert reader. To challenge establishment perspectives where warranted, and enable the general population to understand public policy debates, are among the responsibilities of a scholar, perhaps especially in Singapore where vigorous debate and independent voices are often lacking. Though initially reluctant, being an expatriate Singapore national has helped me fulfill this role.

In 2006, I wrote: “I believe that national identity must have an irrational and not just an economically rational component, coming from emotional ties rather than pragmatic self-interest.[8]

“If I choose to become a member of a nation because it gives me a good job and lifestyle, I am really interested in that nation only as a place, and it makes sense if one day I leave it for another place which can offer me superior conditions and opportunities.

“It is when I stick around when a place cannot guarantee me a good life, or I am concerned with the welfare of others in that place, and try to improve things even at a risk to my own good life (say, I join the political opposition), that I can say I am of the nation, and not just the place.”

I feel the same today. I have been extraordinarily fortunate. As an expatriate, I have not had to sacrifice a good job and lifestyle while training my normal-for-an-academic “critical eye” on policy developments in my home country. There remains a touch of “survivor’s guilt” in my continued efforts to ensure my fellow Singaporeans can enjoy the same freedoms without having to leave home. As I have written before, “When academics speak their mind, society benefits.”

— Linda Lim is Professor Emerita, Stephen M. Ross School of Business, University of Michigan.

Notes

[1] “An economist’s view”, Bridges: Celebrating the Cambridge-Singapore Connection (Oxford and Cambridge Society of Singapore, 2013).

[2] “Singapore’s Heavy-Handed Detentions”, Asian Wall Street Journal,August 17, 1987.

[3] “The School System and Social Structure in Singapore” for Commentary, the Journal of the University of Singapore Society, followed by two articles with Pang Eng Fong in The New Nation paper.

[4] The book review was of The Sun in Her Eyes: Stories by Singapore Women, edited by Geraldine Heng, today a distinguished professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

[5] The Singapore news media was arguably even freer in the late colonial and early post-colonial period, when my grandfather was a journalist, before he had to contend with Lee Kuan Yew’s progressive clampdowns on the Singapore press.

[6] E.g. “Singapore’s Foreign Workers: Are They Worth the Cost?” (Asian Wall Street Journal August 4, 1981); “Political Economy of a City-State” (Singapore Business Yearbook 1981/82); and “Women in the Singapore Economy” (Commentary, 1981).

[7] See, for example, the review of my book of collected essays, Business, Government and Labor: Essays on the Economic Development of Singapore and Southeast Asia (World Scientific, 2018) by Anne Booth, professor emeritus of economics at the London School of Oriental and African Studies, in Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (September 2021). She concludes: “Taken together these 15 papers are a tribute to Lim’s formidable scholarship over a period of more than three decades and especially to her ability to question conventional wisdom and throw new light on important economic policy questions.”

[8] “Singapore: Place or nation?” (Straits Times June 19, 2006).