CHERIAN GEORGE

Political agendas have been internalised in Singapore’s universities. Academics who directly experience censorship and retaliation are not the only ones paying the price.

Singapore’s politically compromised university system has done less harm to me than to several academics I know, and probably many others I don’t. When my career in Singapore was blocked and my employment contract with Nanyang Technological University entered its final months, I contemplated options outside of academia. But what seemed like a dead end turned out to be just a fork in the road. As luck would have it, I veered to an equivalent position in another city, continuing to do what I’d been doing in Singapore, virtually uninterrupted, and with a stimulating change of scene.

Therefore, among the cases I know of political intervention in academic careers in 21st century Singapore, I can’t claim that my plight was the most dire (not that I’d want that dubious honour). But it was probably the most publicly documented, with several insiders coming out a decade ago to quash the notion that I lost my job due to lack of merit. This essay does not contain new revelations. Most of the account has been published before and never been disputed by university administrators and government officials with direct knowledge of what happened.

Selected coverage of the case from 2013–2017.

The publicness of the case makes it a smoking gun in discussions about academic freedom in Singapore. In addition, it brings to the fore a bigger question about knowledge and democratic participation. How much information do citizens need about a problem before they acknowledge it, let alone act to solve it? This is what the student of politics in me finds most fascinating.

There have always been some people, including fellow academics, who resist the truth that Singapore’s leaders can be petty enough to sabotage individuals they disagree with. They prefer the theory that I lost my job because I was just not good enough. I have heard this view spread by word of mouth and seen it pop up in social media discussions.

At first, this hurt. Later, I could contemplate the phenomenon more dispassionately, feeling more intrigued than insulted. I study authoritarian systems, and fate had placed me in the middle of some fascinating research questions. Among them: why do some citizens refuse to recognise autocratic moves for what they are, choosing instead to hang on to rationalisations contradicted by available evidence? You cannot always blame this on government spin — in this case, the state and its agents were relatively silent. Instead, these observers actively participated in the bottom-up creation of pro-regime propaganda to defend the status quo. My personal experience gave me an early, first-hand look at post-truth politics and how agents of doubt shroud evidence-based criticism in clouds of misinformation.

Whether I deserved tenure is a question about which people are entitled to their own opinions. But they are not entitled to their own facts, as the by-now-old adage goes. Regardless of what one feels about the quality of my work or the rigour of my institution’s peer review exercise, the fact is that in 2009, NTU concluded that I met its requirements for tenure. That was their academic decision. What happened afterwards was politics.

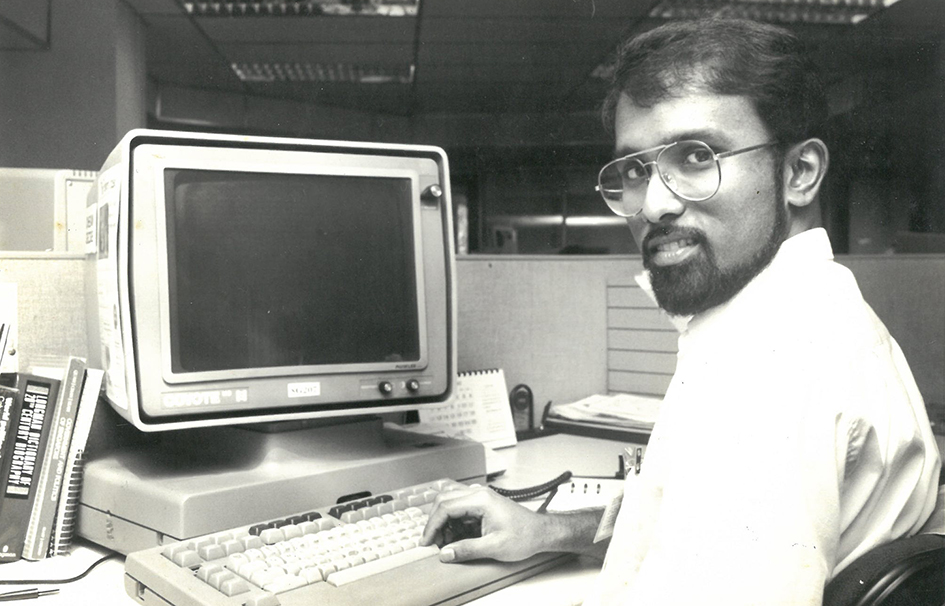

At the Straits Times in the 1990s. In 1999, Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew named Cherian George as an example of journalists who “just go to the computer and type away” and “denigrate the prime minister”.

Tenure and politics

In 2008, four years after I’d joined NTU’s communication school, it nominated me for promotion and tenure (P&T). After a months-long review process, word came through the grapevine that I’d made it. When the official letter did not arrive with the other results in mid-2009, my school pressed the university for an answer.

NTU president Su Guaning invited me to his office for a one-to-one chat on 10 July 2009. He confirmed that I had cleared all academic requirements for P&T and that the university wanted to keep me. But, he intimated, his hands were tied. He seemed mystified about why the government was doing this.

But, he made a few things quite clear. First, I had already met the university’s requirements for P&T. Second, I would therefore not have to reapply, he said — a position I documented in a follow-up email exchange. His decision amounted to a deferment, not denial, of my tenure. He asked for my patience as he tried to find a way around this obstacle. Third, he’d been stopped from awarding me tenure, but “they” hadn’t said anything about promotion, he said with a smile. This, he said, allowed him to go ahead and endorse my promotion from assistant to associate professor.

While it would have been nice if Su had fought harder to protect the integrity of the university’s P&T process, I’ve always been grateful that he at least sneaked my promotion through. Since NTU had no separate criteria for tenure as opposed to promotion, my title change from assistant professor to associate professor was essentially a public statement that I’d cleared the academic hurdle for P&T. This alone should have made it obvious to academic peers who are familiar with the system that I’d been assessed to have merited tenure, or so I thought.

As for why my career at NTU merited government intervention, I can only venture an educated guess. My years at The Straits Times had sealed my reputation as a critic of the government.[1] My first book, Singapore: The Air-Conditioned Nation, written after my first year as a PhD student, meant I remained visible when I entered academia as an assistant professor in 2004. This was the age of blogging — social media had not yet taken off — and I was an active blogger. I continued to write occasional commentaries for mainstream media. Feedback was not always positive. In 2005, The Straits Times published a long analysis piece by me, “Managing civil disobedience”, which sparked an exchange with the Prime Minister’s press secretary, who suggested I was being partisan and trying to encourage civil disobedience. The PMO’s reply in ST’s Forum page was so tangential that it provoked a sociology undergraduate (a government scholar) to demolish it in a letter to the Forum page. But of course, in politics, logic is no match for raw power. And power was not on my side.

At the launch of Singapore: The Air-Conditioned Nation, published by Landmark Books in 2000.

I was also active in civil society.[2] Two months before that July 2009 meeting with Su, I organised a workshop on responsible blogging. At this time, many were worried about the professional standards of newly emergent citizen reporters. I felt that the best way to spread ethical practices would be to enlist the help of serious and respected bloggers like Alex Au of Yawning Bread and Choo Zheng Xi, who had helped launch The Online Citizen. Another guest speaker was November Tan, a nature conservation blogger. I felt that Singaporeans new to blogging were more likely to listen to such role models than to university professors or mainstream journalists. Initially, the idea was well received. A top official at the education ministry even agreed to help circulate the invitation to schools. Professional educators understood the importance of cultivating media and information literacy.

Suddenly, though, political alarm bells went off somewhere. My school leadership defended the proposed workshop as best as they could. But the university decided I could not hold the event on campus, nor use its name, as “the university would not like to be embroiled in controversy in case the contents of the forum touch on sensitive issues”. Alternate hosts also appeared to have received the memo. An NUS head who initially agreed to open his faculty’s doors to the event suddenly stopped replying to my emails. In the end, I used my research funds to pay for a hotel venue.

As I recount such activities, some readers might feel that I should have seen my excommunication coming. In hindsight, subsequent events do look predictable. At the time, though, based on my experience as a journalist, I did not expect political blowback. When I was working at The Straits Times, I had more frequent and serious run-ins with the government. If editors ever received word from on high that I was the wrong kind of journalist for the national paper, they chose not to take the hint.[3] My top bosses, Cheong Yip Seng and Leslie Fong, had the political experience and acumen to manage pressure from the government. Sure, they sometimes sacrificed editorial independence, but they also often held the line — and almost always protected their staff.[4] I had no illusions that my politics would permit me to rise to the editorship, but I never feared for my job. I quit in 1999 and left for graduate school not because my editors made me feel unwelcome, but because my wife and I were ready for new experiences.

Besides, the incidents I describe above may not be what sealed my fate. What some people in government may have found intolerable was that I was heading Singapore’s only undergraduate journalism programme. Not that they could point to any specific problem with NTU’s journalism training. Employers were happy with our graduates and the government never had occasion to question our curriculum. But this was a period when government leaders were insecure about the young in general, and perhaps did not feel enough love from young reporters in particular.[5] Some ministers may have gotten it into their heads that reporters were getting corrupted in school. The most outspoken graduates tended to come from Ivy League colleges and Oxbridge, not NTU — but facts rarely pacify the paranoid, and the PAP has always been prone to irrational fears.

Lee Kuan Yew tries to win over young Singaporeans in an unmoderated televised dialogue in 2006. Most of the participants were young journalists. The event was indicative of the government’s mounting anxiety about losing its influence over young minds.

The reasons I’ve suggested are speculative, but they are consistent with signals I received from my bosses. For example, Su asked me to write a paper about journalism education; he said it might help. (I did; it didn’t.) [6] Then, when my school wanted to renew my term as head of journalism, what we thought would be routine paperwork culminated in another one-to-one meeting in the administration building, this time with the provost, Bertil Andersson. He told me that if he signed off on the renewal request, he might as well board the next flight back to Europe. He also floated an idea: I could, he mused, move to NTU’s Rajaratnam School of International Studies. The government might accept this option because RSIS didn’t have undergraduate programmes, he said. I surmised that my bosses believed the core problem was my supposed influence over journalism undergraduates. I did have a chat with the RSIS director, retired ambassador Barry Desker, who was gracious and welcoming. But I did not pursue the matter because RSIS positions at the time were untenured and would take me too far away from my own field.

Su had suggested I reach out to people in government, so I eventually wrote to the prime minister, asking whether their objections had to do with my NTU position or would apply to all Singapore universities. Lee Hsien Loong passed the buck to the education minister, Ng Eng Hen. This was not reassuring. If Ng had been in the driver’s seat to begin with (as some have suggested to me), it was unlikely that he’d reverse the decision. The upshot was a meeting in mid-2010, with Su, Andersson, and Ng’s permanent secretary, ostensibly in her capacity as a member of the NTU board of trustees. She kept her silence. Also present was the director of human resources, who was taking copious notes.

The main purpose of the meeting, I realised only later when a senior administrator clued me in, was to nuance NTU’s position for the ears of the minister’s emissary. Su clarified that the decision about my tenure was not taken by the government but by him and the trustees. But he did not take back what he had told me earlier — that I was academically qualified for P&T and that pressure had come from outside the university. P&T recommendations are usually rubber-stamped by the president and trustees; the real work is done by the provost’s committee. Andersson chipped in that his panel had given a “clear” green light for tenure. I was being denied it, Su said, because of the “perception” that I posed a “reputational risk” to the university.

With NTU journalism students in Bhutan in 2012 for the school’s annual Go-Far programme, which George created in 2005.

While my tenure case remained in limbo, my work was virtually unaffected. In 2010, I received a Nanyang Award for Excellence in Teaching from the university president. (At the ceremony, Su whispered to me that he hadn’t forgotten about me.) In 2011, since I’d met the requirements for P&T, I felt I should be entitled to the benefits that came with it, including a sabbatical. The university agreed, allowing me and my wife to take up a Rockefeller Foundation residency in Bellagio, Italy. When not distracted by the beauty of Lake Como, I kickstarted a new stream of research, on hate speech. In 2012, I published my second academic book, Freedom from the Press, winning an Asian Publishing Convention award.

My relationship with the communication school, students, and almost all my colleagues were unaffected by the political machinations at higher levels. My work there had always been personally meaningful, and I was happy that my contributions were valued. In my first year, which coincided with the devastating Asian Tsunami of 2004, I had devised a new experiential learning course to report on recovery efforts in Sumatra and Sri Lanka. I created it on behalf of Shyam Tekwani, a dear colleague with conflict reporting experience. I dubbed it Going Overseas For Advanced Reporting (Go-Far) and it became a magnet for donors and a flagship programme of the school.

I also designed and headed a sabbatical programme for media professionals from the region, the Asia Journalism Fellowship, which Temasek Foundation enthusiastically funded as a capacity-building scheme that could also win friends for Singapore. Now hosted by the Institute of Policy Studies at NUS, it has more than 200 alumni; coming back to speak to each new batch remains an annual highlight in my calendar.

Senior colleagues even credited me with the school’s renaming as the Wee Kim Wee School in 2006, in honour of the much-loved journalist-turned-ambassador-and-president who had died the year before.[7] In 2011, my friend Tay Kay Chin and I produced a photojournalism magazine commemorating that year’s general election, with proceeds donated to the school’s Wee Kim Wee Legacy Fund. My name was etched on the donor wall at the entrance of the school not long after I was forced to exit it.

Left: Temasek Foundation chief Benedict Cheong welcomes the first batch of Asia Journalism Fellowship participants in 2009. Right: With Fellows at a reunion event in 2013.

Meanwhile, my third and final contract was running down. If my deferred tenure was not confirmed, I would be out of a job. Andersson succeeded Su as president, and Freddy Boey took over as provost. The new team reneged on Su’s promise, telling the school that I should resubmit an application for tenure. I assumed this was a formality to make right the fiasco of 2009, so I agreed. I had continued to receive glowing annual appraisals and had a stronger teaching and research portfolio compared with the previous attempt.

What transpired came as a shock. Boey’s committee came to the opposite conclusion as Andersson’s three years earlier. To help achieve this, the university had to pretend 2009 never happened. They tampered with my application packet: I discovered that my six-page cover letter, which set out the background to my application for the sake of new reviewers who were not familiar with its history, was removed before any reviewer had sight of it. I only found this out after the result. When I appealed, Andersson agreed that the redaction was improper. His chosen remedy was to ask Boey’s committee to consider my appeal after reading the redacted pages. Not surprisingly, its final decision stood. I was given the customary one-year grace period before being shown the door in February 2014.

A public controversy

I did not go public in the three years between the first and second tenure rounds, but I was quite open in private conversations. Many expressed indignation that a Singaporean could be treated this way even as the red carpet was rolled out to expatriates. Historian Anthony Reid had been the founding director of the Asia Research Institute at NUS when I did a post-doctoral fellowship there. In 2012, he told me he had been offered a visiting fellowship at NTU. Then in retirement in Australia, he liked the idea of another stint in Singapore. But he was troubled by what he’d heard about my case. He had asked his hosts about it, but also wanted to hear directly from me. When I filled him in, he decided to decline NTU’s offer. It was a selfless act of principle by a foreign academic who’d always wanted the best for Singapore’s universities.[8] It was also a touching gesture of loyalty to a junior scholar who had been under his wing a decade earlier, for barely a year.

Public support for me multiplied exponentially the following year. My denial of tenure in dubious circumstances made national and international news. Students launched a change.org petition – behind my back, so I could not be justifiably accused of abusing my position as a teacher to incite agitation on my behalf. Civil society followed up with an open letter to the education minister signed by dozens of respected individuals, most of whom I did not know. The signatories included several academics who must have wondered if their public stand would be held against them by their current or future employers, but added their names anyway.[9]

Some might discount the views of students and civil society as uneducated in the complexities of a rigorous tenure exercise. Harder to dismiss were knowledgeable insiders. Senior faculty in my school, including its two former deans Eddie Kuo and Ang Peng Hwa, rebuked the university. Still employed by NTU, they displayed exemplary moral courage. Similarly, Mark Featherstone, a professor at NTU’s School of Biological Sciences, blew the whistle against the university leadership’s flip-flop. He wrote to the chair of the board of trustees, Koh Boon Hwee, and made his letter public. As Dean of the College of Science, Featherstone had been a member of the provost’s committee that had recommended my P&T in 2009. Based on this inside knowledge as well as publicly available facts, he said, “A purely peer-driven exercise is not what has led to the denial of tenure to A/P George. It is rather the result of an imposition originating outside the University.” External assessors are a major part of the modern tenure exercise, and all six of mine released their detailed reviews of my portfolio. All had recommended tenure. Some had even written that I would have qualified for full professorship in their own universities.

Some of the reactions to the news.

I appreciated these and many other voices of support, especially because of the strength they gave my mother. I had hidden my troubles at NTU from her for almost three years, to spare her anxiety. I finally told her just as the news was about to break in the press. After the initial shock, it must have been a source of comfort for her to know that so many respectable people were on my side.

I mention all this to put into proper perspective my observation that some Singaporeans, including fellow academics, opined that I’d lost my job because I just wasn’t good enough. They were probably a small minority. When I shift focus now to the negative, it is not because the backbiters had a major impact on my own life, but because of what they taught me about how day-to-day authoritarianism works.

Unknowing of public knowledge

Within a year of my departure from NTU in February 2014, I opened up about what had happened.[10] The timing was dictated by Bertil Andersson, who misspoke when a reporter in Europe asked him about my case. I wrote to him with the help of my former schoolmate, the skilled defamation lawyer Adrian Tan (who died in 2023). The exchange of letters elicited a public climbdown by Andersson. More importantly, it allowed me to invite the university to refute the account I was now providing. The relevant evidence was available in various documents. These included the minutes of Andersson’s tenure committee in 2009, and the notes from the meeting of 2010 when the reasons for withholding tenure were explained to me by Su and Andersson in the presence of the education ministry permanent secretary. I declared that I was prepared to waive all confidentiality rights if NTU wanted to release these documents. But NTU has never challenged my account. There are no two sides to this story. There is only one, which you have just read. Everything else is misinformation, spread by individuals whose desire to express an opinion exceeds their patience to honour the facts.

I now wonder whether it was purely coincidental that my research shifted around that time toward the phenomenon of ground support for authoritarian tendencies.[11] Perhaps my early interest in how a culture of mass denial supports authoritarian impunity was partly stimulated by my (relatively trivial, but direct) experience of post-truth politics — witnessing some intelligent Singaporeans’ resistance to readily available facts.

Nowadays, whenever new cases surface of political intervention in academics’ careers, it no longer surprises me that some academics sidle to the defence of the status quo. Such interventions have become more frequent over the past decade: hiring decisions blocked by an opaque security vetting process; foreign faculty denied visas; research projects halted on non-academic grounds. Most experienced faculty in social science or humanities departments have knowledge of such instances. Yet, we hear gaslighting: “I see some critical work being done, so there’s no real problem here.” And whataboutisms: “Even in the West, academics are penalised or censored for being politically incorrect.”[12] And victim-blaming: “We want academics, but not activists.”

When my friends and I produced groundbreaking empirical research in 2021 about the sorry state of academic freedom in Singapore, we heard such responses. Fortunately, many more peers welcomed our survey of Singapore-based academics. Their cooperation helped us produce a report and book chapter of unprecedented depth, about how non-academic sensitivities restrict teaching, research, and outreach. But the state continues to enjoy the support of scholars who are studiously uncritical about academic freedom in Singapore.

AcademiaSG’s report on academic freedom was raised in Parliament by the Oppostion but its findings were brushed aside by the government.

In 2024, I tried to sum up the situation when drafting an AcademiaSG submission responding to an open call from the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on the right to education. Our submission pointed out that in societies such as Singapore, academia is co-opted and captured by power in subtle, stealthy ways:

“These may occur without the arrests, direct censorship, government takeovers, or physical attacks that make news headlines. Instead, they often involve substantial carrots alongside sticks, such that these politically compromising relationships with people in power are welcomed by universities that seek the state’s resources and patronage. … Such dynamics can result in a curious situation where the state suppresses academic freedom with the apparent support of the academic establishment. University administrators internalise the state’s political sensitivities, and devise internal control structures and incentive systems accordingly, to induce their staff to work within politically constrained parameters. The net result is a system that operates mostly through hidden self-censorship.”

The difference between my first and second tenure application outcomes illustrates the trend toward the internalisation of political considerations within university governance. In the first round, NTU’s leaders were honest enough to tell me that they faced pressure by the government. In the second round, NTU owned the decision, acting as if politics had never come into the picture.

I doubt that the higher education sector’s enablers of state domination are mostly motivated by strong ideological commitment. They are probably driven by instincts for self-preservation. They have rational fears that their institutions will lose out in the competition for state patronage. This engenders compliance even in the absence of direct instructions. Most of the petty slights I have experienced since leaving NTU have been initiated by the managements of establishment institutions and their minions. These include university leaders telling event organisers to uninvite me, mainstream media editors vetoing their reporters’ plans to interview me, and so on. Second guessing is rampant. I suspect gatekeepers’ interventions frequently go above and beyond the call of duty. In one case, I am certain of it: when NUS top management blocked a lecture I’d been invited to give in 2018, the education minister told me that no such instruction had come from the ministry and that he’d sent word to the university that it was fine to carry on. He sought me out at a Singapore consulate reception in Hong Kong to let me know this.

Another time, an NTU student society invited me to give a webinar — a routine talk about Singapore politics. Their dean allowed it to proceed, but under strict rules: no external publicity, no recording, and no reporting, not even on social media. Basically, they could organise and attend it, but not let outsiders know. The only rational explanation for these ground rules was that he saw no need to shield his students from me, but he wanted to insulate the institution from external criticism for hosting me, lest I say something controversial. I felt sorry for the students and embarrassed for my peers, that they had to witness such undignified contortions by administrators to protect their own rear ends. I suspect that this sight made a more lasting impression on my young audience than anything I said.

Harder to figure out are those who are not in any management position, but make unkind and unsubstantiated remarks anyway. Again, I suspect this is about self-protection. In this case it’s not their status they need to shield from external threats, but their self-esteem from cognitive dissonance. Singaporeans are consumed by a cult of meritocracy — we need to believe that what we’ve acquired has been earned fair and square in open competition. It can be disconcerting to be presented with evidence of unfair discrimination. If the game is partly fixed against others, it devalues one’s own accomplishments. In academia, once it’s established that there is systemic discrimination against certain lines of enquiry, those who have secured well-rewarded jobs in those fields are forced to accept that they have progressed on a tilted playing field.

It is never comfortable to confront your privilege. Some do, and accept their responsibility to fight for a truly meritocratic system built on the principles of academic freedom. Others declare that the system is fine; it’s the losers’ fault if they fail to make the grade. Most of them don’t intend harm, nor to defend the government. Perhaps they are just defending their own sense of self.

The net effect of these various dynamics is to diminish academics’ acknowledgment of threats to academic freedom and the cost to society. Without strong backing from academics themselves, public revelations of political attacks on universities cause little more than temporary embarrassment for the authorities. Indeed, such exposés tend to backfire. Instead of interfering less, government and university authorities intervene earlier and in the dark of night, nipping potential problems in the bud.

With co-author Donald Low in Hong Kong, receiving copies of PAP v PAP from their printer in Singapore. Two of their planned virtual book talks at NUS were shelved.

After one public relations gaffe when a public lecture of mine was blocked, I heard that an administrator told faculty to check with the department before inviting guest speakers in future. In another case, when a campus group was stopped from holding an already-advertised talk by me and my PAP v PAP co-author Donald Low, our thwarted host was ticked off for not knowing better than to invite us. The bureaucratic logic is impeccable: the way to avoid messy disinvitations is not to invite in the first place. In AcademiaSG’s survey of academics in Singapore universities, almost two-fifths said they did not feel free to invite guest speakers as they wished, of whom more than half reported that their institutions required them to obtain permission before doing so. Such bureaucracy was rarer a decade ago.

Censorious forces take on a life of their own. A decision by one gatekeeper to shut down an academic event or cancel a public intellectual may be misguided and unnecessary, but others confuse noise for signal. In a more pluralistic political environment, with multiple sources of patronage, news about politically motivated interference and censorship could produce enough indignation and resistance to make administrators think twice about intervening the next time. However, in the context of Singapore’s hegemonic, one-party dominance, institutional guardians learn from each new scandal to be increasingly micromanaging. Thus, individuals branded by one institution as “controversial” may find themselves nationally shut out. Random acts of censorship coalesce to form the new normal.

Counting the costs

The system trundles on. If the public controversy over my tenure case has not been repeated, it is probably because university administrators have since learned not to be as open with the victims as Su Guaning and Bertil Andersson were with me. Political vetting also seems to have become more stringent at the entry point, blocking the employment of academics with a civil society background.

The system offers many Singaporean and foreign academics satisfying careers and generates lots of excellent research, while marginalising people whose work is perceived as destabilising to the state’s desired consensus on certain issues. Since the former category (who and what are allowed to flourish) is much bigger than the latter (who and what are not), Singapore’s university sector remains largely self-satisfied and quiescent. But as AcademiaSG’s submission to the UN argued:

“Lack of explicit opposition from universities should not be the end of the matter. We need to remember that academic freedom (like media freedom) is not a right owned by that industry for its own benefit. It belongs to the wider society, who have a right to be informed and educated to the best of their country’s ability, without unwarranted interference by political actors. In jurisdictions where high-performing universities co-exist with tight restrictions on academic freedom, … universities may do well on measures that matter to the global higher education industry such as citations and internationalisation, while under-serving their own societies’ need for independent, critical teaching and scholarship.”

Left: A reunion of past and present Wee Kim Wee School teachers, including Eddie Kuo (seated, second from right), who advised him to apply to Stanford and invited him to teach at NTU as an adjunct before starting his PhD studies; Arun Mahizhnan (seated, extreme left), who invited George to serve as an adjunct research fellow of the Institute of Policy Studies after he returned with his PhD; and Ang Peng Hwa (standing, second from right), the dean who hired George as an assitant professor. Right: in 2022, Ang nominated George for election as a Fellow of the International Communication Association.

Many Singaporeans over the years, from highly placed establishment figures to young readers, tell me they wish I were back working in Singapore. At a personal level, this is always nice to hear. I sometimes wish it too. But if we are concerned about our country, that’s not really the issue. Nobody is indispensable. When we assess the effects of Singapore’s authoritarian management of the higher education sector, we shouldn’t focus only on the human cost to individual academics.

In my case, the enforced exile may have even been a blessing in disguise. It gave my wife and I professional and personal experiences we would never have had if we’d stayed put. It accelerated a shift in my research interests that would have occurred even if I’d stayed in Singapore. Even before leaving, I was excited about pivoting toward the global phenomenon of rising intolerance and hate. While I also maintained an interest in media freedom and censorship, I was increasingly drawn to studying this comparatively. The Singapore state’s excessive interest in me forced me to return the compliment, paying close attention to the multi-dimensional, hegemonic character of resilient authoritarianism. Increasingly, though, I applied the lessons the People’s Action Party taught me to the analysis of media and politics elsewhere.

My preferred approach now is to study big global questions through multi-country case studies. The book that I’m proudest of, Hate Spin (MIT Press, 2016), examined rising religious intolerance in the world’s three largest democracies, India, Indonesia, and the United States. For my book with the cartoonist Sonny Liew, Red Lines (MIT Press, 2021), I interviewed cartoonists from more than twenty countries on six continents. My current book project, contracted to Polity Books (UK), studies counter-polarisation efforts around the world. I doubt my increasingly international research interests would change even if I were to return to Singapore.

Speaking at AcademiaSG’s Knowledge Praxis conference in May 2024 about systemic causes for the lack of critical research on Singapore. The conference video can be viewed here.

My physical and mental shift away from Singapore should not matter in a society that is one of the best educated and best resourced in the world. I graduated from college in the pre-web era, and when overseas travel was a luxury. Today’s young are mind-bogglingly more connected and exposed. I marvel at the intelligence of many Singaporeans coming out of local and overseas universities. New cohorts of Singaporean journalists and academics are capable of producing critical work far surpassing the best efforts of my generation. So I was surprised when I found out from my publisher that Freedom from the Press is still selling. I toyed with the idea of doing a much-needed update, but do not have the time.[13] Other, Singapore-based academics should be doing this work. Unfortunately, the prevailing structure of incentives and disincentives does not favour knowledge production in such areas.

In Singapore, I was the only media scholar with a research agenda focused on local press and politics. Since I left, that space has remained unfilled. At NTU’s and NUS’s media departments (both ranked in the world’s top 25 in the field) the number of scholars whose web pages say they specialise in Singapore media and politics is exactly zero. Kris Olds, a geographer and authority on global higher education who once worked in NUS, had predicted in 2013 that NTU would not find a replacement for me with equivalent expertise and experience in the media politics of Singapore. Perhaps this was the point. Why should faculty members research and teach about this in depth when they can instead focus on, say, the social psychology of information processing among social media users in China and the United States and still satisfy ranking agencies and education policymakers? The same pattern holds, more or less, in other disciplines.[14]

The personal stories recounted by me and a handful of other scholars in this series of essays do not give the full picture. To count the cost of Singapore’s constraints on academic freedom, we need to tally the gaps in Singapore’s intellectual capacity created by the systematic suppression of certain lines of inquiry. Overall, Singapore universities’ contribution to the country’s intellectual life and policy debates is extremely thin, compared to the role of other higher education hubs in their own societies. Most alarmingly, this absence is no longer noticed. Singaporeans — unlike, say, Hongkongers — have no expectations that academia will help them analyse complex domestic issues requiring deep knowledge. The enterprise of critical scholarship is caught in a vicious cycle of poor supply and low demand.

Limited edition memorabilia that George made for fellow travellers.

It is increasingly difficult to find the mental capacity to write on Singapore. But it is also difficult to let it go. While I was in the United States for my PhD studies, my wife visited her former professor, Ambassador Chan Heng Chee, and I tagged along. I may have expressed indifference about returning to Singapore to work; I don’t recall exactly. But I remember clearly Chan’s unhesitating, emphatic retort: “Singapore is in the fibre of your being!” Perhaps she saw something in me that I hadn’t yet acknowledged. It may explain my occasional dips into Singapore Studies and the time I devote to AcademiaSG despite the lack of any professional or material incentive.

I don’t expect the system of political vetting for university jobs to be dismantled soon enough for me to re-enter academia in Singapore. This may not really matter for my career as such, although it has of course been painful to come to terms with the fact that the one country where I cannot count on a fair shake is my own. I’m much more hopeful for younger academics, including those pursuing graduate studies now. Time is on their side. The contradictions are too great to last another generation — between a highly educated population in a vibrant, complex city, and an infantilising system of university governance that confuses the preferences of ruling elites with the public interest.

– Cherian George is Professor at the School of Communication of Hong Kong Baptist University.

Notes

[1] In 1994, the Leader of the House threatened me with contempt of Parliament charges for saying in my “From the Gallery” column that the Speaker could have exercised the guillotine more flexibly in that day’s sitting to allow a couple of interesting debates to continue. Referring to this incident a year later, minister George Yeo said of me, “He had no right to speak to the Speaker as an equal.” He used Hokkien to accuse critics like me of not respecting seniority: “boh tua, boh suay”. (Quoted in “Debate yes, but do not take those in authority as ‘equals’”, The Straits Times, 20 February 1995.) The cumulative effect of what I’d considered moderately critical writing was evident from Lee Kuan Yew’s reaction to a column about multiculturalism and democracy published in The Straits Times in September 1999, shortly after I’d left the paper. He said that if you “denigrate the prime minister at will and say ‘Oh, he’s a duffer, he’s a fool’, ‘we are an alienated people, we are two different societies, etc, etc’ — whether it’s Catherine Lim or Cherian George — and they succeed in undermining the standing of the PM, where do we go from there?” While prime ministers made carefully considered statements, he said, “journalists like Cherian George and Catherine Lim just go to the computer and type away”. (Quoted in “SM – Danger in challenging system”, The Straits Times, 19 September 1999.)

[2] In my Straits Times days, I was a founding member of The Roundtable, a political discussion group. I was also involved in The Working Committee, a civil society networking initiative. As a blogger, I was part of the Bloggers 13 network arguing against tighter internet regulation.

[3] I was promoted and given supervisory responsibilities ahead of most of my peers. Five years into the job, I was entrusted with editing the newspaper’s 150th anniversary supplement. Weighing in at more than 200 pages, it was the most substantial special issue in the paper’s history. I was also asked to act for the chief editor on weekends in rotation with others.

[4] For a rare insider account, see Yip Seng Cheong, OB Markers: My Straits Times Story (Straits Times Press, 2013).

[5] It was probably this climate of anxiety that goaded Lee Kuan Yew to engage young voters, several of them journalists, in an unmoderated television debate in 2006. One of the participants, Ken Kwek, recalls the encounter in this talk.

[6] My paper, “Reflections on Journalism Education” (October 2009), was endorsed by the Wee Kim Wee School’s leadership. Although it had been requested by the university president, the university never responded to it. It is available at SSRN.

[7] Although I did suggest the “Wee Kim Wee School” name at a planning meeting, others may have had the same idea around the same time.

[8] Anthony Reid was the only senior academic who counselled me to publish my dissertation with NUS Press — he felt it was a good university press that deserved more support. Years later I was told that NUS’s Singaporean management had a policy of giving NUS Press less weight than western publishers when counting their faculty’s research outputs.

[9] The signatories included Mark Baildon, Susie Lingham, Charlene Rajendran, Angelia Poon, Teo You Yenn, and Wee Wan-ling at NTU (including its more closely regulated National Institute of Education); Daniel Goh, Philip Holden, Tan Tarn How, and Simon Tay at NUS; Noorashikin Abdul Rahman at Ngee Ann Polytechnic; and young scholars who were (or should have been) potential hires of Singaporean universities, like Chia Meng Tat, Stephanie Chok, Loh Kah Seng, Ng How Wee, and Thum Ping Tjin.

[10] My first account was posted just after I left NTU. I said more at the end of the same year, and in my 2017 book, Singapore Incomplete.

[11] When I was invited to give a keynote address at the World Library and Information Congress in 2013, I titled my talk, “The Unknowing of Public Knowledge”. Observing events such as George W. Bush’s war on Iraq under false pretences, I noted that truth seemed to matter less than assumed by the professional ethos of librarians and journalists.This was a few years before the election of Donald Trump and the Brexit Referendum pushed various information disorders — disinformation, fake news, conspiracy theories, hate propaganda, and so on — right to the centre of scholarly and policy attention.

[12] It is certainly true that universities in liberal democracies are facing an academic freedom crisis. But the threats are from local governments, university trustees, donors, students, and administrators, within a pluralistic national context. An academic chased out of a university with an incompatible ideological bent can still find work in a more welcoming university. In contrast, Singapore operates a system of top-down national blacklisting. Affected academics have to leave full-time academia or leave the country.

[13] There have been developments in Singapore’s media politics that are of major public interest and deserve in-depth analysis. The platformisation of news is a post-2012 phenomenon. The 2021 restructuring of Singapore Press Holdings was the biggest shakeup of national news media in forty years. Other new topics for socially impactful, critical media research include the state’s computational propaganda, foreign influence operations, the impact of short videos on political culture, and the blurring of the editorial-advertising divide in mainstream media.

[14] For a fuller discussion, see my presentation at AcademiaSG’s Knowledge Praxis Conference, May 2024, and my article “Singapore’s powerhouses neglect local intellectual life” in Times Higher Education, 11 January 2018.