Kevin Y.L. Tan

Kevin Tan reflects on his career as a legal academic and his deep involvement in civil society and rights and heritage advocacy.

I stopped counting how often well-meaning friends and colleagues have told me that life would be much better and easier if I minded my own business and kept my mouth shut. And they would be right. But this assumes that I possess an irresistible urge to wade into controversial matters that lead to a head-on confrontation with the state and its authorities. Nothing could be further from reality. I dislike conflict and often wish that others would pick up the cudgels and champion the causes dear to me. But what I disdain more than conflict is the expectation of blind conformity and unthinking obedience, which goes against everything I grew up believing. When I graduated from university in 1986, Singapore was only 25 years old. Our generation of graduates would, I thought, work side-by-side with the state in the next phase of nation-building. Alas, that was not my destiny. This is why.

At the beginning: studying law

When I matriculated at the Faculty of Law at the National University of Singapore in 1982, it was an exciting time to be in university. Singapore, still young, had just weathered the rough 1970s – OPEC oil embargo, student protests, left-wing activism, and all – and the economy was on the mend.

We students were filled with great hope and idealism. We were privileged to have a university education — only 7% of our cohort made it there — and we were convinced that it was our destiny to use what we learnt to better Singapore, adding our voices to the chorus of national progress and development. Today, this all sounds naïve and silly, but many truly believed it. Few aspects of Singapore society were cast in stone, and the possibilities were tremendous. Everyone counted, or so we thought.

I enjoyed life at the university and did relatively well. I was active in the students’ Law Club, served as Academic Secretary, and revived the long-defunct Singapore Law Review, becoming its Editor-in-Chief. I was also appointed student editor in the Faculty’s Malaya Law Review, getting my first taste of journal work and authoring academic articles.[1] I inaugurated the first Singapore Law Review Annual Lecture in 1985[2] as well as a series of lunchtime ‘brown bag’ lectures.

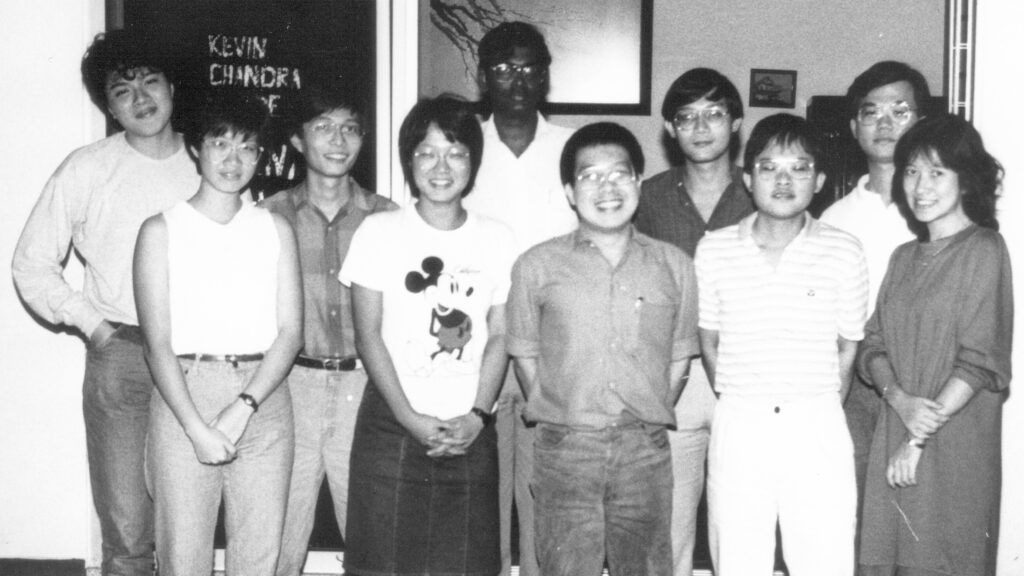

The Editorial Board of the Singapore Law Review (SLR), 1986. While still a student, Kevin revived the journal and became its Editor-in-Chief.

Into academia

At NUS Law, some teachers strongly urged me to consider an academic career. By my final year, I was quite sure that an academic life of teaching and research would suit me well, so I did not think too hard. I enjoyed the study of law but was attracted to the less commercial aspects of it: Jurisprudence, Comparative Law, International Law and Intellectual Property Law. I was deeply drawn to social policy, history, politics and their interplay with the law.

Dauntingly, there was no mentorship for young academics. You were dropped into the deep end of teaching and committee work, and expected to somehow stay afloat. No one guided me on how to prepare for classes or lectures.

On my first day at work, a member of the administrative staff gave me my keys and showed me to my office. I was slated to teach Constitutional Law (not my strongest subject), the Singapore Legal System and Introduction to Legal Method. Less than half an hour after settling in, my former teacher, Walter Woon dropped in on me and recruited me as a contributor for his new book on the Singapore legal system.[3] I was pleased but surprised since I was the newest member of the staff. Walter wanted a chapter on Singapore’s constitutional history:[4] ‘You have nine months.’ I finished it in six and Walter asked for a second chapter, on Singapore’s Parliament.[5] In 1998, Walter asked me to take over as editor of the second edition of this pioneering volume.[6]

To Yale and back

My first year went by smoothly and I enjoyed teaching immensely. Soon, it was time to think of graduate studies. Back then, law academics were not required to obtain doctorates before being appointed Lecturers (the equivalent of Assistant Professors today). All you needed was a Master of Laws (LLM) degree. Weeks of research at libraries and speaking to colleagues led me to conclude that I should do my graduate studies in the United States for a greater breadth of experience. The new Dean tried to dissuade me, urging me instead to go to his alma mater — University College, London — but I demurred (maybe too candidly) and it was probably over this issue that I acquired a reputation for non-compliance. I was not prepared to accept my seniors’ advice unquestioningly and would break with tradition if I thought it necessary.

I decided to go to Yale Law School because it had an outstanding reputation for training academics. It was exceedingly difficult to get in because of the very small class size — about 26 each year. In fact, only four other Singaporeans had managed to get a place — S Jayakumar (later Dean and then Minister for Law) in 1965; Molly Cheang (1966), Tily Shue (1980) and Soon Choo Hock (1981). But when I delightedly showed my acceptance telegram to the Dean, he just stared and asked me if Yale was ‘any good’? Dumbfounded, I could only mutter that Professor Jayakumar had told me that it was.

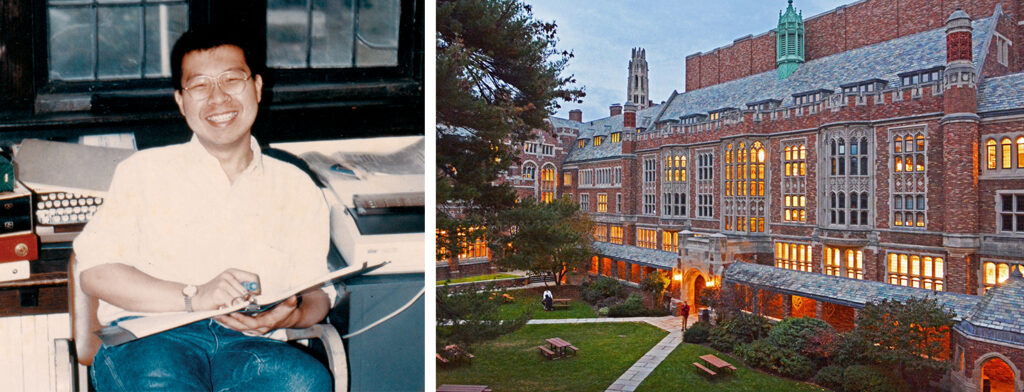

Kevin Tan in his Yale Law School dormitory room, 1987.

Within a week at Yale, I knew that I had made the right choice. I was constantly challenged by the incredible intellectual energy and originality of the faculty and students. I enjoyed classes, especially those in public international law and constitutional law, and became close to Professors Michael Reisman and Bruce Ackerman. I signed up for as diverse a range of courses as I could: International Law, Constitutional Law and English Legal History (taught by the visiting John, later Sir John, Baker).

I did well enough to be accepted into the Doctor of the Science of Law (JSD) programme and had to decide if I would work under Professor Reisman (international law) or Professor Ackerman (constitutional law). When I received news from NUS that I was slated teach Constitutional Law on my return, the choice of subject became obvious. I decided to write a thesis on Singapore’s Constitutional History with Ackerman.[7] I asked the Dean for at least another year to work on my thesis, but the reply was an emphatic ‘No’. I thus had to negotiate with Yale to write my thesis and submit my drafts from Singapore. Thankfully, Professor Ackerman was prepared to supervise me from afar.

Connections and visions

While teaching at NUS, I got to know Lam Peng Er, a political scientist who joined NUS in the same year as me. We got along very well despite our different personalities, drawn together by our mutual concerns about Singapore generally, and Singaporean scholarship and intellectual life in particular, and our love of music, good sound, the theatre and good books. Peng Er also connected me with contemporaries at the Arts Faculty, who have since become long-time friends and collaborators: Huang Jianli (History), Kwok Kian Woon (Sociology), and Wee Wan-ling (English Literature) — as well as others like Tan Tai Yong (History), Albert Lau (History) and Bilveer Singh (Political Science).

Peng Er left to do a PhD on Japanese politics at Columbia University the same year I left for Yale. He was allocated an apartment at the edge of Harlem. On most weekends, I left New Haven for New York and slept on the couch in his living room. We went to the theatre and concerts, visited museums and bookstores, and talked all night about what we would do when we returned to Singapore. Being so deeply committed to Singapore, we were convinced that privileged local academics like us were responsible for developing Singaporean scholarship. We should not sit on the side-lines and watch our expatriate colleagues dominate this space.

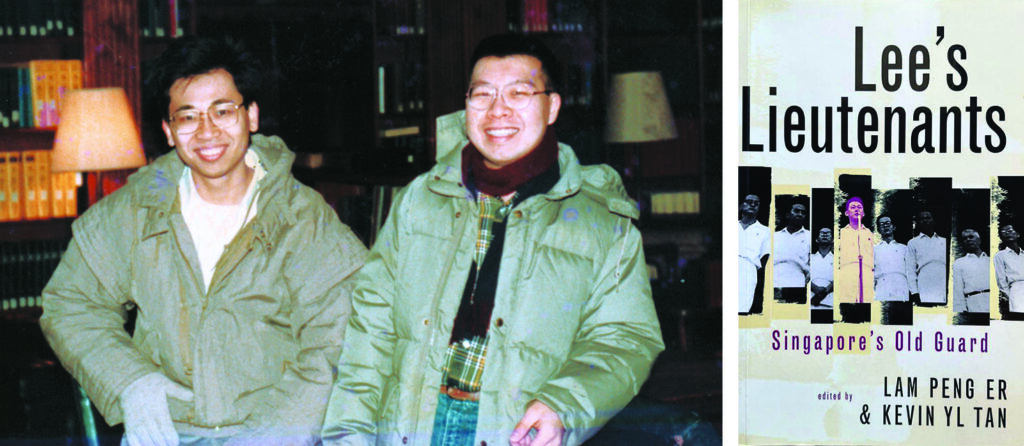

Kevin Tan at Yale with Lam Peng Er, who was studying at Columbia at the same time. Conversations between the two friends gave rise to many years of intellectual collaboration, including their edited volume, Lee’s Lieutenants (1999).

Peng Er and I resolved to pool our resources and connections to bring young fellow scholars into a multi-disciplinary collaborative enterprise that would act as a substantial intellectual catalyst for research into the humanities and social sciences in Singapore. Only in our mid-20s, we somehow found the temerity – some would say ‘arrogance’ or ‘stupidity’ – to think we could pull this off.

By May 1988, Peng Er and I had mapped out three volumes of collected essays that we hoped would draw together scholars of our generation in a collaborative enterprise. The first would be a book about a revolutionary new institution which the government was pushing – the elected presidency. The second, a book about the roles played by Singapore’s first-generation political leaders. A third on the theme of youth in national discourse, policy and institutions. Because Peng Er had still to complete his PhD and I, my JSD, it would take us almost a decade to realise two of these volumes.[8] The third, with a working title of Forever Young, may never be written.

Back at NUS

I returned to Singapore in June 1988 and nearly got lost trying to get to my office. The new MRT lines had opened, and many roads were rerouted or became one-way streets. The Dean told me that I was wasting my time with my doctoral thesis. I retorted that as a career academic, I would have to supervise doctoral theses at some point; and if I had never worked on one myself, I would not make a good supervisor. Unconvinced, he warned that my JSD counted for nothing and that if I hoped to get promoted, I would need to keep up with publications, teaching and committee work. As if to make sure I would give up, the Dean assigned me to teach one more subject than everyone else and appointed me to a host of committees. This kept me very busy.

The University’s Multi-Disciplinary Committee, for instance, met every month. I learnt two very important lessons attending these meetings. First, that scholars trained in one discipline did not often find it attractive to work with scholars in another discipline and it was hopeless to force them to do so. Second (and more importantly), university departments and faculties are designed as silos. For scholars to advance in their careers, they need to be acknowledged and recognised as experts in traditional and established fields. Anyone who did multi-disciplinary research risked being ‘disowned’ or ‘unclaimed’ by their departments and having their work count for nought in the promotion and tenure stakes.

My biggest contribution to this Committee was to propose that as so little was being or could be done to get our colleagues to collaborate, we should wind up the committee up. To my surprise, all the members, including the Chair, agreed. We abolished ourselves. I knew that much as I was much attracted by collaborative multi-disciplinary work, I would need to focus primarily on being recognised for my ‘hardcore’ legal work and competence, before pursuing this interest as a side-line.

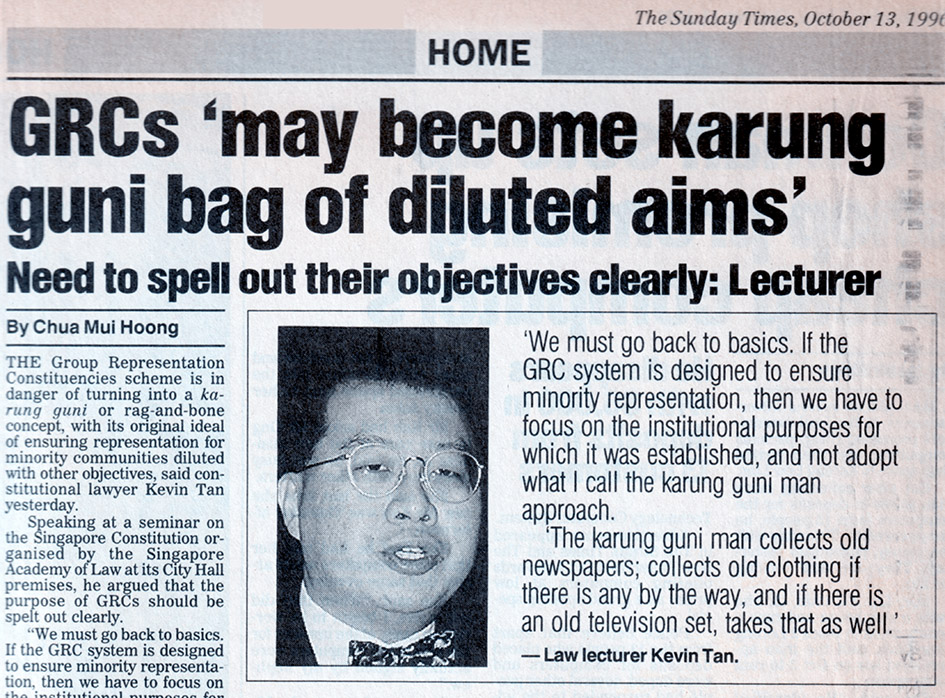

The 1980s and 1990s were a particularly exciting time for constitutional lawyers in Singapore. The government introduced the Non-Constituency MP Scheme in 1984, the Group Representation Constituency Scheme in 1988, and the Nominated MP Scheme in 1990. A number of us became involved in public debates on these schemes. I was also closely monitoring the developments in the elected presidency. I willingly accepted invitations to speak on these changes and to appear in interviews and debates and invariably caught the eye of our political masters. Well-meaning colleagues began warning me that I should steer clear of politics and not comment on anything the government was doing lest I be targeted for retribution. Yeo Kim Wah, a senior history academic in the History Department, warned me: ‘Don’t write about anything concerning Singapore politics after 1959!’

None of this made sense to me. As a scholar ostensibly specialising in Singapore’s constitutional law, I could not remain silent. That would be utterly irresponsible. We should not just be ivory-tower scholars whispering in echo chambers. Was it not our duty as intellectuals to engage actively and publicly in the marketplace of ideas? Innocently, I believed that if we conducted ourselves responsibly, objectively and without backing any political party, we, the citizens, had a right to a voice in public discourse.

In June 1994, I was promoted to Senior Lecturer with tenure and was thus due for a sabbatical. I returned to Yale to wrap up my dissertation in December 1995 and discovered that I was the first Singaporean to earn a JSD from Yale. I was also one of the very few members of the Law Faculty with a doctorate in law, but this attainment counted for nothing (as the Dean had warned), and it was not till the Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Professor Chong Chi Tat (another Yalie) found out about it that he insisted that the news be publicised.[9] Ironically, almost 30 years later, I have not yet had the pleasure of supervising a single PhD student at NUS.

Kevin Tan considered it a duty to apply his expertise to media conversations on major constitutional reforms such as the Group Representation Constituency system.

Today’s academics will find it difficult to understand just how powerful the Dean was in those days. There were no faculty promotions or tenure committees: one’s fate was largely dictated by whether the Dean felt you were ‘ready’ to be promoted. We were all told that we needed to excel in teaching, research and service, but it was unclear what counted towards ‘excellence’. I taught more than most of my colleagues, published more than everyone and served on numerous committees as well, but it never seemed to count as much for me as it did for others. This all changed after 2000, when the Law Faculty suffered the shock of six faculty resignations, including mine.[10]

I had settled down to teaching Public Law (Constitutional and Administrative Law), and the Singapore Legal System and Legal Methods. Occasionally I was asked to help out with Criminal Law as well. In the mid-1990s I floated two new courses. The first, co-taught with Terry Kaan, was ‘Law and Society’, an inter-disciplinary course on the role of law in society, largely inspired by the approach of American scholar Lawrence Friedman. The second, which I co-taught with Thio Li-ann (my closest collaborator in Public Law) was what we imagined was the first course on international human rights in Singapore. To our surprise, the Law and Society course proved extremely popular, even though NUS Law students were famous for favouring commercial subjects. Indeed, when the Law Faculty was asked to offer cross-faculty modules to non-law NUS students, we were asked to take in more students.

The second course was something I had always wanted to teach. I was frankly quite tired of being told — mostly by foreign commentators — that we did not enjoy any human rights in Singapore. These easy tropes made for popular consumption and critique but did little to advance Singapore’s discourse on human rights. Li-ann was also very keen, as was Craig Scott, a professor from the University of Toronto visiting NUS in 1996. Between us, we cobbled together a most innovative course involving the teaching of the same course synchronously and in real-time across the oceans, with NUS on one end and the University of Toronto on the other. This would be done by leveraging the internet. We called it the ‘Global Classroom’, and this excited everyone in the upper echelons of NUS since it would be the first time such a semester-long course was being organised anywhere in the world.

All new courses needed to be approved by the University and this course was about human rights, a subject no one in NUS was prepared to touch with a ten-foot pole. Li-ann wanted to name the course ‘Vindicating Human Dignity’. I vetoed this because it would draw the wrong type of attention. Capitalising on the interest generated by the big ongoing discussions over Asian values and human rights, I proposed ‘Law, the Individual and the Community: A Cross-Cultural Perspective’. It was approved without question.

This was one of the most enjoyable courses I have ever taught, but after its first run, in the academic year 1997–1998, there was no more budget to run the course synchronously. The leasing of the line from Singtel proved prohibitive. I took it offline and ran it asynchronously with Craig for the next two years till I resigned in 2000. In the subsequent courses we were able to include Martin Scheinin of the Abo Akademie University in Turku, Finland and Abdullahi An’Naim of Emory University and their students.

The Roundtable

In 1990, Lee Kuan Yew stepped down as Prime Minister and was succeeded by Goh Chok Tong, who promised a ‘kinder, gentler Singapore’ with a more consultative form of government. For many of us, this was most refreshing news. Maybe there was hope for civil society after all. In June 1991, George Yeo (then Acting Minister of Information and the Arts) made his famous ‘Banyan Tree’ speech:[11] ‘When state institutions are too pervasive, civic institutions cannot thrive. It’s necessary to prune the banyan trees so other plants can grow …’

My friends and colleagues were much encouraged by these signals. At the end of 1993, a few of them got together to establish an independent political discussion group called The Roundtable.[12] Koh Su Haw, my former student and a former member of the PAP’s Youth Wing, established another political discussion group, called the Socratic Circle. Though Socratic Circle submitted its application for registration later than the Roundtable did, it received the Registrar’s approval for registration earlier.

The Roundtable’s two convenors were Raymond Lim, my former colleague at the Law Faculty (and later PAP government minister) and Tan Kim Song, an academic economist (now at the Singapore Management University) who had been at Yale with me. Later, Kim Song invited me to join. Although membership was small, it was very active in engaging politicians informally over closed-door dialogue sessions, and publicly through op-eds in the local newspapers. I served two terms as Treasurer and one term as President, and remained a member till we voluntarily wound up in 2005 because of the numerous restrictions which the Registrar of Societies placed on us.

Right: Kevin’s permit to speak on the opening day of Speaker’s Corner. This was inaugurated while he was President of the Roundtable, the group who had proposed the creation of ‘free speech venues’.

One notable Roundtable initiative was for ‘free speech venues’ in Singapore,[13] which was initially given short shrift by the authorities,[14] but was later implemented as the Speakers’ Corner at Hong Lim Park. As the inauguration of Speakers’ Corner took place during my Presidency, I had the honour of reading a press statement on behalf of The Roundtable at Hong Lim Park that day.

One law that troubled us deeply was the Public Entertainments Act (renamed the Public Entertainment and Meetings Act in 2000, before becoming once again the Public Entertainment Act in 2017). Under the Act, the Police established a Public Entertainment Licensing Unit (PELU) to control the issue of licences for public entertainment. Among other things, the Act required anyone wishing to organise a public meeting to obtain a police permit. This prior restraint made it difficult for The Roundtable to organise talks or panel discussions that we could throw open to the public.

In November 2000, I decided to avoid these restrictions by organising and moderating a private panel discussion on the Societies Act and the future of Civil Society. I booked a small meeting room at the RELC and invited panellists including novelist Catherine Lim and Tan Chong Kee, founder of Sintercom. At first, I thought we would issue invitations to friends and supporters to avert any possibility of having our meeting classified as ‘public entertainment’. Then one member, James Gomez, suggested that we could publicise the event online but also state that it was ‘by invitation’ only. If anyone wanted an invitation, they should write to James. A small crowd of about 35 attended, but there were two men at the back of the room whom I did not recognise. I assumed that they were James’ friends.

In April 2001, my fellow Roundtablers and I were called up to ‘assist the police’ in their investigations for our allegedly providing public entertainment without a licence.[15] It was ridiculous, and I maintained throughout that it was a private event. It was not open to the public and I had paid for the facilities personally. It was, I argued, like organising a private birthday party. The poor inspector who questioned me — looking like he very much preferred to be elsewhere — then told me that some ‘non-invitees’ had been present. Ah! Those two guys at the back! I asked him if he had sent plainclothes policemen to sneak into my function, but he denied any complicity.

My final argument was that when events are held in a relatively public place — like the RELC, or an HDB void deck — strangers may chance upon it and ‘gate crash’, but this did not transform a private event into a public one. After about an hour, he typed up my statements for signature. He thanked me for my assistance and muttered that he was now off to ‘catch some real crooks’.

As President of The Roundtable, I publicly shared my views on legal and constitutional issues and was widely quoted in the mainstream press. These topics were an extension of my public utterings about, among other things: the continued admission of Queen’s Counsel in Singapore;[16] the legal profession;[17] the rights and interests of Malays under the Constitution;[18] electoral system and oppositional politics;[19] the role of Select Committees in Parliament;[20] the GRC scheme;[21] the NMP scheme;[22] citizens’ rights,[23] free speech under Article 14 of the Constitution;[24] the validity of Asian Values;[25] and of course, the problems associated with the Elected Presidency.[26] In 2001, I stepped down as President of the Roundtable, and was succeeded by lawyer Chandra Mohan K Nair, but continued to serve on the Executive Committee as Treasurer.

When President Ong Teng Cheong (left) needed constitutional advice, Professor Tommy Koh (second from left) sought the help of law academics, including Kevin Tan.

The Elected President

Early in 1994, I received a call from Prof Tommy Koh to meet at the Institute of Policy Studies on a matter of some urgency. When I arrived, my colleagues Walter Woon, Valentine Winslow and Thio Li-ann were also there, as were some lawyers from Drew & Napier, with Cavinder Bull representing Joseph Grimberg who was unable to attend. Tommy told us that a constitutional matter was looming. President Ong Teng Cheong would need some legal help. Were we willing to advise him gratis?[27]

That was how I became one of President Ong’s constitutional advisors. The matter concerned the amendment of the President’s powers under the Constitution and was to be referred to a new special constitutional tribunal to be established.[28] Joe Grimberg and Walter Woon argued the case, while the rest of us helped with legal arguments. By the time the case went before the tribunal, I had left for Yale to complete my JSD dissertation. The Special Constitutional Tribunal, established under the new Article 100 of the Constitution, held that President Ong did not have the power to block the proposed amendment to Article 22H in the Constitution.[29]

The President’s informal panel of lawyers and advisors became more or less defunct after the hearing, but President Ong continued to invite Walter and myself to discuss constitutional questions for several years afterwards.

Leaving – and returning to – NUS

As President of the Roundtable, I was very much in the news, proffering views on voting rights and citizenship, the elected President, GRCs, free speech and a host of other subjects. In one such interview, I attracted Lee Kuan Yew’s ire. On 30 July 1999, a long interview I gave to Chua Mui Hoong was published in The Straits Times.[30] In it, I made the case that the design of the Elected Presidency scheme was gravely flawed and that a better institution could have been designed for the purpose of safeguarding the reserves. I suspect that it was the timing of the interview and what I said about the institution being ‘confusing’ that irritated the Government. Less than two weeks earlier, former President Ong had given an interview to the now-defunct Asiaweek magazine, outlining his problems in doing his job properly and getting government information about the reserves. The Government was visibly upset by these revelations, and while it would be improper to attack the President too harshly, I was fair game.

Quoting me out of context, Lee stated in Parliament that I was wrong and he was ‘alarmed’ at what I might be teaching my students at NUS.[31] Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong called my views ‘ill-informed’.[32] The next day, the Dean (a serving PAP Member of Parliament) told me that my job was ‘on the line’ because ‘the Old Man’ said I didn’t know what I was talking about. I was flustered, but decided to go down fighting, so I told the Dean that I stood by every word I said, and would be more than happy to debate the Senior Minister ‘any time, any place, and in any medium’ because ‘I was right and the Old Man was wrong’. I think he was shocked by what he considered my insolence, and told me to leave his office. I never found out what he told Lee, but from that day on, my life at the Faculty became progressively more miserable.

In June 2023, Kevin Tan delivered an AcademiaSG Lecture on the Singapore Presidency. In the 1990s, Lee Kuan Yew castigated him for his critique of Elected Presidency system, but Tan’s analysis stood the test of time. In 2016, the Menon Commission suggested that the government should consider returning the Presidency to its traditional ceremonial role.

In June 2000, I gave up my tenured job, resigned and left to work for the late Tan Chin Tuan (TCT), former Chairman of OCBC. Tan had been wooing me for some months. Given how unhappy I was feeling at NUS, I decided to leave for totally unchartered territory. At TCT’s family office, my job was to provide long- and short-term political risk analysis for the investment team. I was also tasked with looking into the operations and missions of TCT’s charitable foundations. I also continued to do some teaching at the Wee Kim Wee School of Communications and Information at the Nanyang Technological University at the behest of its Dean, my old friend Ang Peng Hwa. There I co-taught a most enjoyable module on Media Law and Policy with Cherian George, another old friend from The Roundtable.

Two years later, after TCT fired me over a disagreement over how I was running an academic project he sponsored, I called up Dean Tan Cheng Han of NUS Law to ask if I could return to academia. He immediately agreed to appoint me as an adjunct Associate Professor to teach Constitutional Law. I was deeply grateful for his generosity and jumped right back into teaching and academic research and writing. Notwithstanding my two-year absence from NUS, I continued as if I had never left. It has been 22 years since I returned, and I continue to be actively engaged in academic life, teaching, researching, publishing, and mentoring younger scholars. In 2007, I was approached by Barry Desker, Dean of the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies at the Nanyang Technological University, to offer courses on international law and international human rights at the school. Since I was only an adjunct professor at NUS, I had sufficient freedom and flexibility to teach in both places.

Heritage, history and advocacy

After I stepped down as President of The Roundtable, my old friends Willy Lim and Kwok Kian Woon asked me to become President of the Singapore Heritage Society (SHS). I was reluctant — I wanted a break — but there is no rest for the wicked. I joined the Society in May 2001 and was unanimously elected President that August, with my old friend Wee Wan-ling as my Vice-President.

At the time, I thought that heritage advocacy would not embroil me in any serious confrontations with the state. How wrong I was! Three years before, the SHS had been at the forefront of a campaign to stop the Singapore Tourism Board (STB) from turning Chinatown into a ‘theme park’.[33] This generated a groundswell of angst and discontent among Singaporeans who lamented the pace at which historical parts of Singapore were destroyed or ‘Disneyfied’.

The fierce exchange in letters to The Straits Times[34]culminated in a public forum organised jointly by STB and the Revitalisation of Chinatown Committee at the Kreta Ayer Community Centre on 1 Feb 1999. The event was emotionally-charged. Sociologist Chua Beng Huat got so irritated that he literally told STB’s Kenneth Liang to ‘shut up’. Architect Tay Kheng Soon infamously took the STB’s Chinatown Revitalisation Plan (beautifully bound in Chinese silk brocade), slammed it on the table and told STB to ‘stop this nonsense’. The media did not report on what transpired, but the public anger forced the STB to back down and seriously rethink its plans. To cool things down, SHS issued a press statement largely agreeing with STB on three basic premises – that heritage and tourism were not diametrically opposed; that Chinatown needed revitalizing to help businesses in the area; and that history could not be re-created. But SHS did not necessarily agree with STB on how this should be done.[35] At the same time, SHS stalwart and pioneer walking guide Geraldene Lowe-Ismail published Chinatown Memories,[36] with a grant from the STB. These debates were also captured in a slim volume published by SHS in 2000.[37]

The Singapore Heritage Society Exco at a retreat in Malacca, 2003.

At about the same time, the SHS had launched another campaign to save the National Library. In 1998, it was announced that a new university — the Singapore Management University — would be built in the city centre, occupying several major plots of land stretching from the Cathay Building all the way to Raffles City. The National Library would be relocated to a new building to be constructed in Victoria Street. What would become of the fair-faced brick National Library building on Stamford Road? In 1999 its demolition was announced,[38] once again triggering discontent.

The Preservation of Monuments Board (PMB), a government statutory board on which I served from 1998 to 2003, had considered the Library building for preservation, but based on the criteria for assessment, the Board could not recommend its preservation as a national monument. I distinctly remember how, during our debates, my fellow PMB and SHS member, Kwa Chong Guan argued that the criteria should be amended to include ‘social memory’. I was much intrigued by this suggestion and agreed that the existing assessment was overly focused on the physical rather than the intangible value of the building under consideration.

The authorities could not understand. Why were people so angry about destroying a not-too-attractive 35-year-old building? Chong Guan was right; people were upset because the state was destroying a building that held so many wonderful social memories for them.[39] It was almost like destroying a shared past. Almost immediately, members of the public came up with various ways to save the building from destruction, including re-routing Stamford Road and realigning the proposed tunnel to Penang Road.[40] But the Ministry of National Development stuck to their guns and declared on 6 March that the building would have to go.[41] The state won — it always would — but this angered people from all walks of life. The Society documented this particular campaign in another book published in 2000, Memories of the National Library.[42]

Although I was not directly involved in either campaign, I followed events very closely. I grew fascinated with how the public spontaneously engaged with these issues and with their pasts. It became clear to me that public policy advocacy was not the sole preserve of public intellectuals and elite do-gooders, but could involve the masses. However, the masses would only be engaged if they had a clear stake. And for this to happen, they had to first know the stakes and the issues. Public education was key. And for proper education, we needed good research.

Dinesh Naidu, Executive Secretary of the SHS in my first two terms of office, pithily coined what became our tagline: Research • Education • Advocacy. In the coming years we would focus on knowledge production through research, public education through publications, talks and exhibitions; and advocacy in appropriate situations.

However, first I had to put the Society on a proper footing. While Kian Woon, as former President, had done a wonderful job raising the intellectual tenor of the Society and its public profile, the Society’s administration needed attention. When I took over, I discovered that quite a few of those listed as its members were either dead or had left Singapore. After removing the names of all those who had not paid any membership dues for three years, we were left with a grand total of 22 members. Not an auspicious start. While a small and committed group could well punch above its weight, there is also strength in numbers. In my first term, I was feeling my way around, getting to know the key players in the field and understanding the dynamics of state-society interactions. In that time, I focused on getting our Executive Committee (Exco) members to be more engaged in state boards and committees and to also get a sense of the government’s tendencies with respect to heritage, conservation and preservation.

Just before our 2003 annual general meeting, I organised a strategic retreat in Malacca. By this time, we had more than doubled the membership to 56. After three gruelling sessions, we resolved to rebuild the membership base by offering members a smorgasbord of activities (including an annual tour), a copy of the monthly Asia Heritage magazine[43] and books published by the SHS. Between 2003 and 2011, we organised numerous talks, heritage walks and local tours, published almost a dozen books[44] and organised several regional heritage tours[45] and exhibitions.[46] By the time I stepped down as President in August 2011, we had a membership of 180 and the SHS had become a household name in the heritage firmament. It was a lot of hard work, often taking up more time than my day job.

On an archaelogical dig, 2010.

I was particularly happy to promote archaeology as an integral part of our historical studies and investigation, incorporating it as part of the assessment process in the new National Heritage Board Act. This was thanks largely to the highly-energetic and enterprising Lim Chen Sian, who joined us in June 2003 fresh from his archaeological studies in Boston.

In terms of advocacy, we had nothing as exciting as the raucous Chinatown or National Library battles. We focused on less high-profile buildings and structures, like arguing about the proper windows to be installed for shophouses in Bussuroh Street, or not naming the new MRT station at Temple Street ‘Chinatown’ station, or protesting the destruction of Regent Alfred John Bidwell’s ‘Butterfly house’ on Meyer Road. Two of our protests did, however gain national attention.

The first involved the original Changi Prison, built in 1936. The Ministry of Home Affairs announced in 2003 that this needed to be demolished to make way for the new Changi Prison Complex. At that time, I was serving my final term as a member of the PMB. The impending demolition came to our attention even though Changi Prison was not a national monument. Even if we thought it suitable to do so, it would have been too late to try to gazette it as one. Nonetheless, the Board felt strongly that key elements should be preserved, as it was an iconic building with international significance. We advocated the retention of the west wall, which was nearest to the main Old Changi Road (and hence most visible). I proposed that the front gate be cut out and inserted in the middle of this wall, to retain all key elements of the prison – the gate, the wall and the two turret watch-towers – with minimal impact on the new complex. The Ministry of Home Affairs rejected our proposal — they would keep just the turrets. That was preposterous: a prison without a wall?

Shortly afterwards, I ended my final term with the PMB and felt freer to comment. In the meantime, the Australian press began a campaign to ‘save’ Changi and wanted to interview me. I was happy to oblige and repeated my suggestion. Australian war veterans began bombarding their Minister for Veterans’ Affairs with concerns. The matter found a champion in Alexander Downer, Foreign Minister, whose father had been interned at Changi. At every opportunity, the Australians lobbied the Singapore government to reconsider, and by the end of the year, a compromise was reached. The west wall would indeed be retained, complete with turrets, and the gates would be transferred from the north wall… just as I had originally suggested.[47]

Remnants of the old Changi Prison were finally gazetted as a National Monument in 2016.

The second piece of successful advocacy had to do with the Berlayer Beacon at Labrador Park. To attract more tourists from China, STB decided to demolish this and replace it with a replica of Lot’s Wife, a rock outcrop that rose out of the sea channel near Keppel Harbour. The Board assumed — wrongly in our Society’s view — that this was the landmark that ancient Chinese mariners referred to as Longyamen or Dragon’s Tooth Gate. I drafted a very short letter to the press criticising this attempt at replacing a genuine heritage object (the Beacon which was built in 1938) with a fake tooth made of fibreglass. The Straits Times published this on 8 April 2005[48] and set in motion a chain of events which led to the retention of the Beacon and a relocation of the ‘Dragon’s Tooth’.

In the final year of my presidency of SHS, two other major heritage issues emerged. The first concerned the land to be vacated by the Malaysian Railway (KTM) as it transferred the Tanjong Pagar Railway Station to Singapore, along with its 24km track. The second involved the government’s decision to exhume over 4,000 graves at Bukit Brown Chinese Cemetery to make way for a highway. I was only briefly involved in these two state-civil society encounters, which saw an even bigger groundswell of activism by the citizenry.

After stepping down as SHS President, I hoped for more free time. But I soon became involved in setting up the Singapore National Committee of the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). ICOMOS, the technical arm of the World Heritage Committee (established under the World Heritage Convention), is a select body made up of ‘heritage professionals’. In May 2014, I was elected the first President of Singapore’s national ICOMOS committee, and went on to serve several terms. In 2018, I was also invited by the Urban Redevelopment Authority to sit on its Heritage Identity Partnership (HIP) Committee, where I remain today.

With Yale-NUS College students in 2017.

Today and beyond

On the academic front, I remain extremely busy. At any time I am working on four to five different book and article projects. I have served on the editorial boards of several law journals and have been Editor-in-Chief of the Asian Yearbook of International Law (2012–2017) and the Asian Journal of Comparative Law (since 2020).

Looking back, I imagine that my various encounters with the state — through the Roundtable, the Heritage Society and now ICOMOS and even in the subjects I teach — must have made me appear an ‘oppositional’ figure. I have never been a political partisan, but I suppose anyone who does not agree completely with the Government must necessarily be seen as a ‘critic’ or ‘opponent’. At the very least, one is seen as a ‘trouble-maker’, since the state makes no distinction between what Tommy Koh calls ‘good trouble’ and ‘bad trouble’. Well, I suppose that if I sat on the side of the state or were a civil servant, I too, would find me rather irritating.

— Kevin Y.L. Tan teaches at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore and at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, specialising in constitutional and administrative law, the Singapore legal system, international human rights and Singapore legal history. He has written or edited more than 60 other books on law, history and politics.

Notes

[1] ‘Computers and Their Legal Impact’ (1983) 4 Singapore Law Review 9–18 (with Richard Tan Ming Kirk); ‘Copyrightability of Books and Tapes in Singapore’ (1984) 5 Singapore Law Review 14–26; ‘The Family, Social Policy and the Law in Singapore’ (1985) 6 Singapore Law Review 2–11; and ‘Economic Development and the Changing role of Lawyers: A Comparative Study of Singapore, Japan and the People’s Republic of China’ (1986) 7 Singapore Law Review 68–90.

[2] Justice Punch Coomaraswamy, ‘The Perils of Drafting’ (1985) 6 Singapore Law Review 40–50.

[3] Walter Woon (ed), The Singapore Legal System (Singapore: Longman, 1989).

[4] ‘A Short Legal and Constitutional History of Singapore’ in Walter Woon (ed), The Singapore Legal System (Singapore: Longman, 1989) 1-33.

[5] ‘Parliament and the Making of Law’ in Walter Woon (ed), The Singapore Legal System (Singapore: Longman, 1989) 37–66.

[6] Kevin YL Tan (ed), The Singapore Legal System, 2 ed (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1999).

[7] Kevin YL Tan, ‘The Development of Constitutional Government in Singapore: 1945–1990’ unpublished JSD dissertation (Yale Law School, 1995).

[8] Kevin YL Tan & Lam Peng Er (eds), Managing Political Change in Singapore: The Elected Presidency (London: Routledge, 1997); and Lam Peng Er & Kevin YL Tan (eds), Lee’s Lieutenants: Singapore’s Old Guard (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1999). The latter volume was updated, revised and published in 2018 by the Straits Times Press.

[9] ‘NUS lecturer gets law doctorate from Yale’, Straits Times 12 Feb 1997, at 18; and ‘Evolution of good government’ The New Paper 19 Feb 1997, at 24; The AlumNUS, Apr 1997, at 60.

[10] ‘6 resign from NUS law faculty’ Straits Times 18 May 2000, at 2.

[11] Anna Teo, ‘How to make Singapore a home not a hotel’ Business Times, 21 Jun 1991, at 26; ‘Lively civic society needed to develop a soul for S’pore’ Straits Times, 21 Jun 1991, at 32.

[12] Anna Teo, ‘Professionals form citizens’ think-tank’ Business Times, 29 Dec 1993, at 2.

[13] See Cherian George & Zulkifli Baharudin, ‘The case for free-speech venues’ Straits Times, 20 Jan 1999, at 40.

[14] Casimir Rosario, ‘Free speech venues may threaten order’ Straits Times, 28 Jan 1999, at 40. The Roundtable responded to this letter from the Director (Public Affairs Division) from the Ministry of Home Affairs with, Zulkifli Baharudin & Kevin Tan, ‘Free-speech venue an incremental step’ Straits Times, 3 Feb 1999, at 43. See Rosario’s riposte in ‘No lack of avenue to express views’ Straits Times, 12 Feb 1999, at 52.

[15] ‘Police summon members of the Roundtable’ Straits Times, 18 Apr 2001.

[16] ‘Should admission of QCs to S’pore Bar be tightened’ Straits Times, 11 Jul 1990, at 24.

[17] ‘Soul-searching time for lawyers’ Straits Times, 27 Nov 1993, at 32.

[18] ‘Views on Malay higher studies’ The New Paper, 13 Jun 1989, at 6; ‘Some fear “erosion of rights”, others see it as “self-reliance” Straits Times, 30 Jun 1989, at 24; and ‘Non-Malays say proposal is fair but many sympathise with Malays’ Straits Times, 6 Dec 1989, at 34.

[19] ‘Opposition’s by-election strategy: Will it work this time?’ Straits Times, 17 Feb 1996, at 23; ‘Hiving off MacPherson’ Straits Times, 10 Feb 1996, at 34.

[20] ‘1990: A watershed of sorts for Parliament’ Straits Times, 22 Feb 1991, at 33.

[21] ‘GRCs may become karang guni bag of diluted aims’ The Sunday Times, 13 Oct 1996, at 28.

[22] ‘Are NMPs still relevant?’ Straits Times, 21 Sep 1991, at 30.

[23] ‘Why more power should be given to Singaporeans’ Straits Times, 1 Mar 1997, at 33.

[24] ‘Licence to Speak or Not’, Straits Times, 18 Nov 2000: H14–H15; ‘No right is absolute, says varsity don’ The Sunday Times, 24 Jan 1999, at 31; and ‘The politics of free speech’ The New Paper, 27 Nov 1999, at 4.

[25] ‘The Asian values debate revisited’ Straits Times, 28 Jan 1996, at 4; and ‘Human Rights: The East Asian Challenge’ Straits Times, 18 Feb 1996, at 1.

[26] ‘Presidency “a confusing institution”’ Straits Times, 30 Jul 1999, at 46.

[27] Zuraidah Ibrahim, ‘Pre-trial conference sets hearing on amendment to elected president law’ Straits Times, 22 Feb 1995, at 3; and Ramesh Divyanathan, ‘President Ong seeks clarification from court on powers’ Business Times, 23 Feb 1995, at 2.

[28] Constitutional Reference No 1 of 1995 [1995] 2 SLR 201.

[29] Zuraidah Ibrahim, ‘3-judge tribunal rules against President’s case’ Sunday Review, 21 Apr 1995, at 1 & 4.

[30] Chua Mui Hoong, The Friday Interview, ‘Presidency “a confusing institution”’ Straits Times, 30 Jul 1999, at 46.

[31] Lee Kuan Yew, Speech on ‘Issues Raised by President Ong Teng Cheong at his Press Conference on 16th July 1999’, Singapore Parliamentary Debates Reports, 17 Aug 1999, col 2067 where he said, ‘ was surprised to see this academic constitutional lawyer from our university – and I was alarmed when I read he is teaching our students constitutional law – that he had not read our own Constitution and that he believed that the President was partially ceremonial and partially executive. If he had read the provisions, he would know that in no Article or sub-Article of the Constitution is the President given executive power. He has a certain veto, a certain blocking power.’

[32] Goh Chok Tong, ‘Prime Minister’s Statement on “Issues Raised by President Ong Teng Cheong at his Press Conference on 16th July 1999”’, Singapore Parliamentary Debates Reports, 17 Aug 1999, col 2037.

[33] ‘Chinatown as theme park’ Straits Times, 22 Nov 1998, at 37.

[34] See Yap Kim Sang, ‘Let us have a say in plans for Chinatown’ Straits Times, 30 Nov 1998, at 30; Gayle Mak Yuet May, ‘Maintain life and soul of Chinatown’ Straits Times, 5 Dec 1998, at 79; ‘Chinatown “won’t become a theme park”’ Straits Times, 12 Dec 1998, at 68; Michael TH Lim, ‘Plans to enhance Chinatown’ Straits Times, 12 Dec 1998, at 81; Tan Sai Siong, ‘Don’t freeze or pretty it up, let it grow to meet our needs’ Straits Times, 18 Dec 1998, at 10; Yap Kim Sang, ‘Plans should not be for tourists only’ Straits Times Weekly Overseas Edition, 26 Dec 1998, at 23; Dinesh Naidu, ‘Don’t sanitise Chinatown’ Straits Times, 22 Dec 1998, at __; and Michael TH Lim, ‘An authentic Chinatown for all’ Straits Times Weekly Overseas Edition, 2 Jan 1999, at 23.

[35] ‘Rival bodies close rift over Chinatown’ Straits Times, 21 Feb 1999, at 11.

[36] Geraldene Lowe-Ismail, Memories of Chinatown (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 1998). The first edition of this volume carried illustrations by Lidia Leung Mei-Ying. It was reprinted in 2011 with illustrations by Derek Corke by Talisman Publishing; and in 2016 with illustrations by Graham Byfield.

[37] Kwok Kian Woon & CJ Wee Wan-ling (eds), Rethinking Chinatown and Heritage Conservation in Singapore (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2000).

[38] M Nirmala, ‘National Library building to go’ Straits Times 14 Mar 1999; and Tan Hseuh Yun, ‘Library must go for 2 key reasons’ Straits Times, 20 Mar 1999; Tan Hsueh Yun, ‘National library building will not be conserved’ Straits Times, 27 Mar 1999.

[39] Rebecca Lim, ‘Here we watched the girls go by’ Straits Times, 14 Mar 1999.

[40] ‘Want to save parts of the library?’ Straits Times, 22 May 1999; ‘New plan for Bras Basah Park offered’ Straits Times, 8 Oct 1999; ‘Alternative plan: some key features’ Straits Times, 25 Jan 2000; ‘Have park and campus?’ The New Paper, 25 Jan 2000; ‘Design contest may throw up new ideas’ Straits Times, 8 Feb 2000; ‘Rescue attempt’, The New Paper, 8 Feb 2000; ‘Library building is worth saving’ Straits Times, 10 Feb 2000; ‘Proposed scheme: preserving the Library’ Straits Times, 11 Feb 2000; ‘What’s the point?’ Straits Times, 11 Feb 2000; ‘S21 vision at stake in library issue’ Straits Times, 12 Feb 2000; ‘There’s hope yet for park and library’ Straits Times 15 Feb 2000; ‘False hopes about park and library’ Straits Times, 17 Feb 2000; ‘When rules get in the way of good alternative ideas’ Straits Times, 18 Feb 2000; ‘The library crusader speaks up’ The New Paper, 18 Feb 2000;

[41] Lydia Lim, ‘National Library Building will have to go’ Straits Times, 7 Mar 2000.

[42] Ho Weng Hin, Kwok Kian Woon & Tan Kar Lin, Memories and the National Library (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2000).

[43] When we were in Malacca, one of my daughters spotted a notice pasted on a pillar advertising this new magazine and drew my attention to it. I took down the contact details and was soon in touch with Selene Lee, the publisher. Selene is the wife of noted Malaysian historian Lee Kam Hing.

[44] These included: Tisa Ng & Lily Tan, Ong Teng Cheong: Planner, Politician, President (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2005); Kay Gillis & Kevin YL Tan, Book of Singapore’s Firsts (Singapore: Talisman, 2006); Tan Wee Kiat, Edmund WK Lim & Kevin YL Tan, Singapore’s Monuments and Landmarks: A Philatelic Guide (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2007); Olimpiu G Urcan, Surviving Changi: EE Colman – A Chess Legacy (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2007); Leon Comber, Through the Bamboo Window: Chinese Life and Culture in 1950s Singapore and Malaya (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2009); Leon Comber, The Triads: Chinese Secret Societies in 1950s Malaya and Singapore (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2009); Hidayah Amin, Gedung Kuning: Memories of a Malay Childhood (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society & Helang Books, 2010); Loh Kah Seng & Liew Kai Khiun (eds), The Makers and Keepers of Singapore History (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society & Ethos Books, 2010); and Kevin YL Tan, Spaces of the Dead: A Case from the Living (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society & Ethos Books, 2011).

[45] These included tours to Johor, Malacca, Penang, Perak, Kuala Lumpur, Medan, Surabaya, East Java, Riau, and Sumatra.

[46] An Ingenious Reverie: The Photography of Yip Cheong Fun (2006); A Life to Remember: Lim Boon Keng (2007); Vignettes in Time: Singapore Maps & History Through the Centuries (2009); William Farquhar: First Resident of Singapore (2010);

[47] For an academic study of the battle to save part of Changi Prison, see Joan Beaumont, ‘Contested Trans-national Heritage: The Demolition of Changi Prison, Singapore’ (2009) 15(4) International Journal of Heritage Studies, 298–316.

[48] ‘No dubious replica, please’ Straits Times, 8 Apr 2005.